Additional Thoughts

It’s often noted how different the medieval Robin Hood is from the character we find in movies and television. It’s true to an extent. The Robin Hood of these plays (or play) does not fight cruel Norman overlords. He doesn’t freely distribute the money from his robberies to poor, starving villagers. Robin doesn’t impose his road tax on rich and powerful knights, barons or even abbots and bishops (although his fight with a friar does continue the anti-clerical tradition of the ballads) – no, this Robin Hood forces a working stiff, a potter, to pay his toll. Robin justifies his actions because he is the chief governor under the greenwood tree. No wonder the publicity for Angus Donald’s 2009 novel Outlaw billed Robin Hood as “The Godfather of Sherwood Forest”.

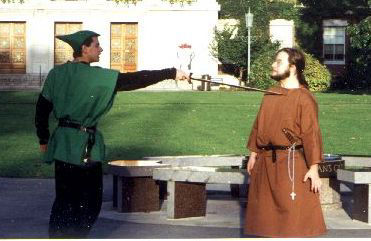

But if in some aspects the early Robin Hood legend might be darker than the do-gooder children’s hero we often find in the 21st century, the Robin Hood of the friar and potter plays is also funnier. Dobson and Taylor describe the tone of plays as “comic buffoonery”, and when scholars discuss these plays the word “bawdy” is almost always used. Friar Tuck suggests he’ll have his way with a lady free, and there’s an extended discussion on whether the potter is a cuckold. Both plays are essentially about two people insulting each other and then getting into fights. The 2001 Robin Hood and the Friar production by PLS did not have to stretch the text that far to showcase the comic potential inherent in the play

Oh, and the friar’s weapon of choice in these comic fights? The quarterstaff. The online edition of the Oxford English Dictionary offers Copland’s play as the earliest use of the word. But the word quarterstaff should be well familiar to modern-day Robin Hood fans. It’s Little John’s signature weapon in the later ballad Robin Hood and Little John – a ballad very much in keeping with the style of these plays. Little John’s association with the staff continues in film and television versions of the legend.

Little John is the only one of Robin’s band (not counting any new recruits) to be mentioned by name in these plays. He also appears in all the early ballads too. One can imagine that when Robin asks for his Merry Men to listen to his tales of adventure that he’s addressing other characters from the ballads, such as Much the Miler’s Son or Will (he of many surnames, but Scarlet is the most familiar to us). But maybe not. The May Games raised funds by selling liveries. The villagers showed their allegiance to Robin Hood by buying badges or strips of cloth. Perhaps the Merry Men that Robin addresses are not the heroes of legend, but the audience themselves – all now made honorary Merry Men by the liveries they have purchased. Interaction between characters and the audience is something that continues in the Robin Hood production, for example it’s a stock part of the many Christmas pantos that Robin appears in.

Earlier I compared the ballad tradition with the performance tradition. But that’s not a fair division, is it? These plays are linked to ballads, perhaps an adaptation of them. The “Robin Hood meets his match” ballads – as many others have noted – are likely an outgrowth of the May Games. But it’s more than that. At the 2001 Robin Hood conference, I didn’t just see a production of Robin Hood and The Friar. I also saw a “talk-sing” recitation of A Gest of Robyn Hode by folk singer Bob Frank. Much like when I saw the plays, Bob’s version of the Gest radiated with life and humour that I hadn’t always seen in the text itself. That was performance too. The ballads are performance – the Gest and the ballad version of Robin Hood and the Potter both ask the audience to listen, not read – listen.

Tuck and Marian only turn up in later surviving ballads, but these plays suggest that the Curtal Friar ballad is much older than the copies that survive. And would audiences have really kept characters separate between different media -- in the plays, but not the ballads -- for so long? When comic books are adapted to radio and television, the adaptations sometimes create new characters and concepts that are later inserted back into the comics within a few years – not a few centuries. Who knows what we’d find if more medieval ballads survived. Perhaps the main differences between the plays and the ballads are ones of practicality. Arrow-catching dogs? It’s an easy enough concept to sing about, but not so easy to dramatize on stage. The nature of the stories may change based on what the strength of each medium is, but for the general audience, ballads or plays – it would all be the same Robin Hood.

Contact Us