Robin Hood in 1950s British and American Comics: Beards, Violence and Religion

Bellamy’s Robin Hood greatly resembles Errol Flynn with mustache and goatee. (And to my eye, Bellamy’s sheriff even more closely resembles Melville Cooper’s sheriff, also from the 1938 film.) In his introduction to the collected edition, Holland speculates that the Flynn look may have been to distance itself from the Richard Greene TV series at the time which they did not have the rights for. However, another British comic book Robin Hood at the time – the one in Thriller Comics Library series by Amalgamated Press – also had a mustache and goatee.

American publishers – Magazine Enterprises, Quality Comics, National (or DC) Comics and Charlton – all opted for the clean-shaven, clean-cut 1950s Robin Hood, although it was only Magazine Enterprises that eventually secured media tie-in rights to the Richard Greene TV series, The Adventures of Robin Hood.

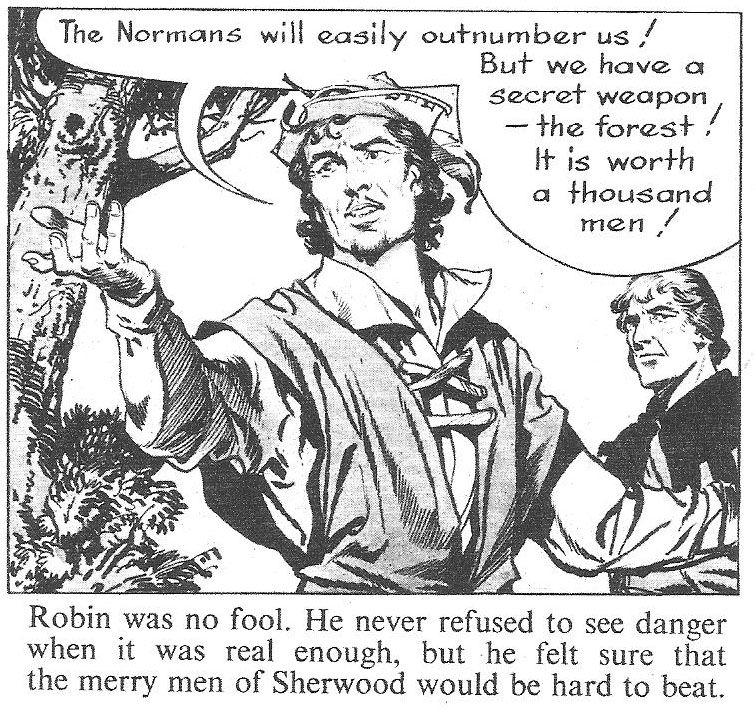

Facial hair isn’t the only difference between American and British depictions of the outlaw. While both the American and British comics minimize Robin’s insurrection by making most of his enemies “robber barons”, Prince -- and later King -- John plays only a minor role in the Swift comics (as with Gilson’s novel). In the American comics, the “usurper” Prince John is a constant presence. But in the Makins and Bellamy series, John’s right to rule (either as regent or later as king) is not truly called into question. Also, American Robin Hood comics of the 1950s often had Robin battling tax collectors – with the taxes called “unjust” and “illegal”. In a country founded by a revolution against the monarchy and corrupt taxes, Robin’s fight against taxes and the crown might seem more patriotic than it would be for British children.

Another difference is in the depiction of violence. Marcus Morris, the Anglican minister who launched Swift and its earlier and more famous companion magazine Eagle got his start by penning an article condemning American comics -- "Comics that bring Horror into the Nursery". But by the mid-1950s, most American comics had been cleaned up and were voluntarily following a “Comics Code” to tone down the violence. Death just wasn’t a factor in the world of 1950s American code-approved Robin Hood comics.

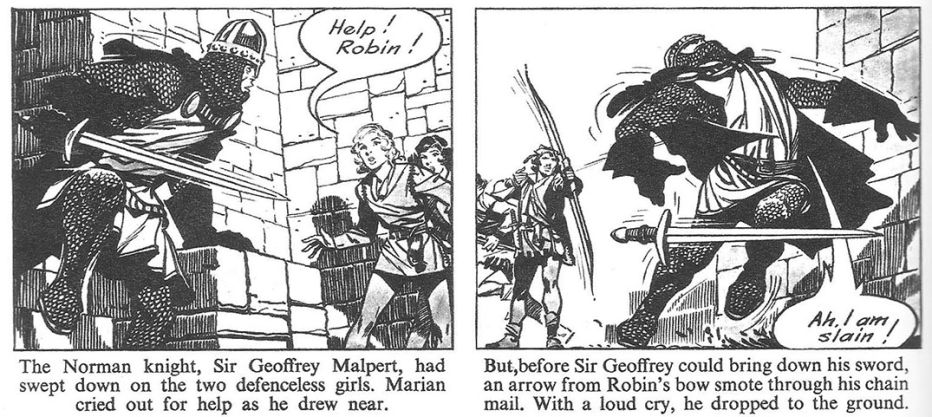

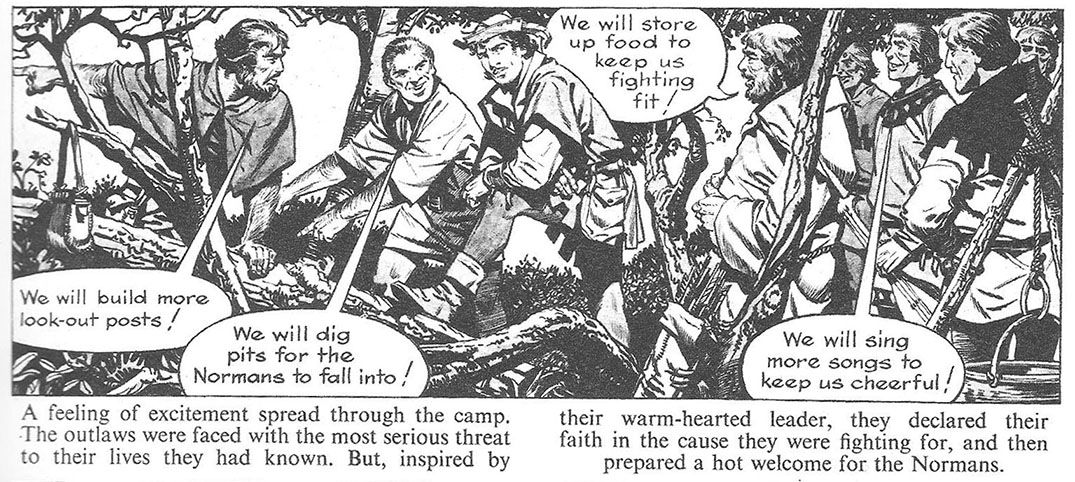

But in Swift comic magazine (even though Britain had gone further than the United States by passing laws which explicitly censored comics) – both Robin and his enemies killed on occasion. The Swift comics were never gory about death – no blood gushed from arrow wounds. In the third episode we see Robin’s father killed on panel, but based on the angle of the sword on panel, it’s almost possible to imagine that the Norman had just clubbed Lord Alfred with the sword’s pommel rather than slashing him with the blade. In the 26th installment, a Merry Man is “mortally wounded” as a hail of Norman arrows whiz past him, but none of the arrows is actually seen entering the body. Later on, death was depicted more clearly as Robin dispatches Robert the Wolf with an arrow to the heart. But no matter how tastefully depicted, it was a departure from the death-free American comics. (The 2008 collected edition features an afterword “Bowdlerized Bellamy” which shows how death was edited out of the 1960s reprints of the Makins and Bellamy strips in Treasure magazine. Most strikingly in the reprint, the gallows where the sheriff unsuccessfully tried to hang the outlaws was changed to a less-fatal “whipping post”.)

As the product of a publishing empire founded by a clergyman hoping to instill Christian principles in his audience, the Robin Hood of Swift comics lacks something that was a constant presence in the legend – religion.

Yes, Friar Tuck is still there. He’s too famous to be excluded. And it might not be so surprising that the clerical villains of the ballads – the villainous monk, the Prioress of Kirklees, the Abbot of St. Mary’s and the Bishop of Hereford – are nowhere to be seen.

But the positive aspects of religion are missing too. Robin Hood does not say three masses daily or risk capture to go to church as he does in the ballads. The virtuous archbishop of the 1952 Richard Todd film doesn’t show up to cast the church in a good light. King Richard – although he wears a cross on his surcoat – is only said to be “fighting overseas”. The Crusades were mentioned by name in the 1950s Richard Greene TV series and the almost-completely secular Middle Ages of the 1950s American Robin Hood comics. Even when King Richard is clearly disguised as a monk or abbot (as can be seen by the great cloak, and the ballad tradition), the nature of his disguise is never mentioned. One might assume the heroes are Christian, but you never get definitive confirmation of that.

Tuck’s declaration “God save the Earl!” in the second episode is the sole reference to a higher power. (Elsewhere in Swift, readers could follow the adventures of “The Boy David”, so the lack of religion in Robin Hood was not reflective of the magazine as a whole.)

Contact Us