CHANGES TO THE ROBIN HOOD LEGEND

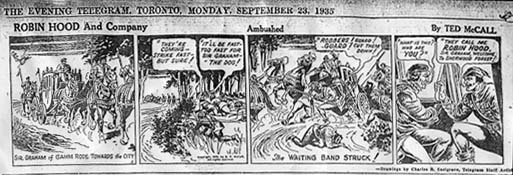

Robin Hood in Comic BooksRobin Hood has also starred in several comic book series and has inspired other comic book characters. On September 23, 1935, the Toronto Telegram introduced a new comic strip -- Robin Hood and Company. The writer was journalist Ted McCall and the first artist was Charles Snelgrove. The series had limited distribution in the United States. (The Wilson Daily Times in Wilson, North Carolina started running it in March 1936.) It was also reprinted in Great Britain, France and Belgium. The series began with a typical highway robbery and ended on August 10, 1940 with Robin Hood freeing Cypriot slaves and returning to England with a new companion, Blackbeard!

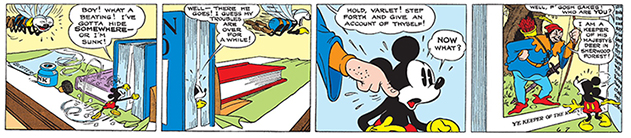

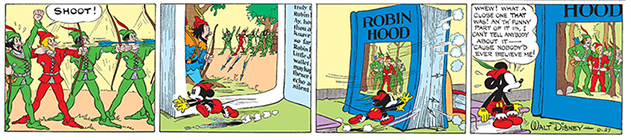

In 1941, Robin Hood and Company was resurrected in comic book form, and is in fact, one of two comic books that can make the claim of being Canada's first comic book. Originally in black and white, the comic book reprinted the earlier Telegram adventures. Later McCall told new adventures, eventually in colour, along with back-up features such as "Kip Keene, Star Rookie of the Men of the Mounted". Wartime import restrictions had blocked US comics from entering Canada. When those restrictions were lifted in 1946, the Canadian comic book industry collapsed and the series was cancelled for good. In 1936, Robin Hood’s appearances in the Toronto Evening Telegram weren’t just confined to Ted McCall’s Robin Hood and Company. On Saturdays the Tely carried the Mickey Mouse comic strip that was syndicated in many other papers for their colourful Sunday editions. (Religious laws in Canada blocked publication of newspapers on Sunday.) The Mickey Mouse strip might have been officially credited to Walt Disney, but the tales of comic adventure were actually plotted and drawn by Floyd Gottfredson and scripted by Ted Osborne. Mickey had discovered a formula that caused things to grow and shrink. Through a series of mishaps, Mickey had been reduced to the size of a fly. He was being swatted at by a fly which had been transformed to giant size. In the strip dated June 7, 1936 (although it appeared in the June 6 Toronto Evening Telegram) Mickey hid from his attacker in the pages of a picture book – a Robin Hood book.

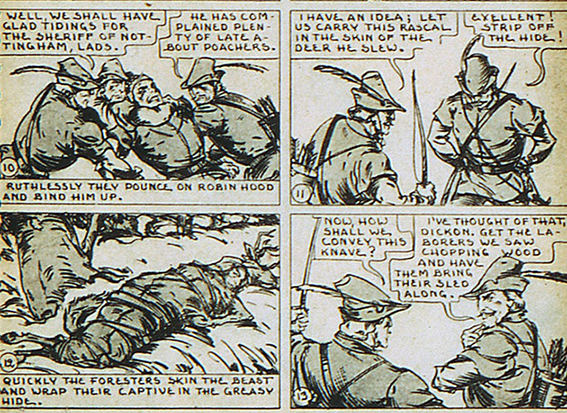

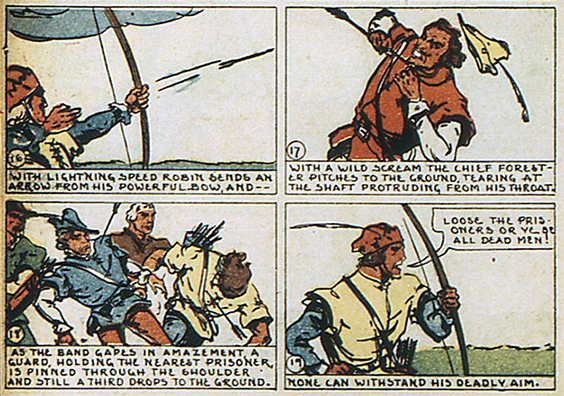

Mickey is startled when the book’s illustration comes to life and a forester arrests Mickey. The mouse is led before the Sheriff of Nottingham. Alongside Mickey is another prisoner – a beggar who was caught poaching. The sheriff orders that the captives are to be executed. But Mickey lures the guards away by pointing to a passing pedlar and claiming that the pedlar is Robin Hood in disguise. As the guards chase after the pedlar, Mickey and the poacher escape on horseback. The poacher reveals that he is really Robin Hood. Encounters with foresters, escaping execution and Robin in disguise are all classic elements of Robin Hood stories. Once Robin and Mickey make it back to Sherwood Forest, yet more Robin Hood tropes are introduced. Mickey is forced to fight Little John in a quarterstaff duel, and then Mickey accidentally does well in an archery tournament. But then the comic strip contrasts the values of the medieval ballads with those of the 20th century. Robin orders Mickey to rob a traveller and the visiting mouse balks at that suggestion.  Mickey goes through with the robbery, besting a stranger knight in yet another quarterstaff duel. The knight gladly offers Mickey more money than the mouse felt comfortable asking for. The stranger acknowledges Mickey’s discomfort at the outlaw life and he writes a note for Mickey to take back to Robin Hood. It reads “This man defeated me in fair combat! He is a gallant fighter and a credit to your band! But I command that never again shall he be sent to rob wayfarers!” All are astonished that the note is signed by King Richard. Mickey Mouse then goes on the sort of mission that he thinks Robin Hood should undertake – rescuing a damsel in distress. But it turns out that the damsel-in-distress business is a racket, designed to lure gallant heroes into marrying more than willing damsels. Mickey has no interest in getting married, and then fights the guards to avoid rescuing the damsel – a Minnie Mouse lookalike named Maid Minerva. The castle guards, the Merry Men – they all push for Mickey to get married. And when Mickey ends up insulting everyone, he has to flee from all the characters. Mickey finds the place where he entered the book and leaves in the strip dated September 27, 1936.  And what was the insult that set everyone off? Not for the first time Mickey insists that “you guys are nuthin’ but a bunch o’ poor illustrations in a cheap picture book!” Not so cheap, perhaps, as the cover to the picture book resembles N.C. Wyeth’s masterful illustration in the 1917 edition of Paul Creswick’s Robin Hood novel. Robin Hood would appear in many comic books and comic strips, although few had the style and wit of Robin’s adventure with Mickey Mouse. Classic Robin Hood starring were retold in more serious form in New Adventure Comics from the publisher which would eventually be called DC Comics. New Adventure (later just Adventure) Comics was an anthology comic book, and the Robin Hood runs from issue 23 (cover dated January 1938) until issue 30 (cover dated September 1938). The first and last two installments are in black-and-white while the middle installments have the more expensive colour printing. The artwork by Sven Elven has an illustrative quality, slightly closer to Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth than most artists from the Golden Age of Comic Books could manage. That's appropriate since the stories themselves retell adventures from the ballads and later children's novels. The first few issues deal with Robin's encounter with the foresters -- an extended version of the ballad Robin Hood's Progress to Nottingham and later novel adaptations. Unlike the ballad version, Robin does spare most of the foresters' lives, but the violence is still more explicit than what would be permitted in DC Comics just a couple years later, once moralist groups attacked comic books much like they criticized Robin Hood folk drama a few centuries earlier.

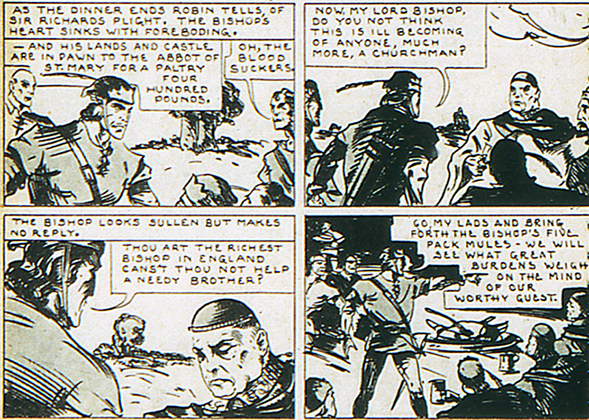

In later installments, Robin would go onto meet Little John and Friar Tuck in scenes common to ballads, books and movies. In the final two installments, the story turns to one of the earliest ballads for inspiration -- A Gest of Robyn Hode. Robin helps Sir Richard of the Lea repay his debt to the Abbot of St. Mary's. In later comic adaptations, the abbot is replaced with a secular figure to avoid offending religious groups. But not only is the evil abbot in New Adventure Comics, the outlaws also rob The Bishop of Hereford, straight from another ballad.  Also during the 1940s, Robin Hood came to star in the seventh issue of the fondly remembered series, Classics Illustrated [originally known as Classic Comics]. Like the serial in New Adventure Comics, Classics Illustrated drew on classic ballads and children's books. Constantly reprinted, this comic was republished with new art in 1957. The Classics Illustrated format has been copied many times -- Dell Comics published a similar one shot in the 1960, and Marvel introduced their own line of Classics in the 1970s with Robin starring in the 7th issue. In the 21st century, there have been other comic book retellings of Robin Hood for children.

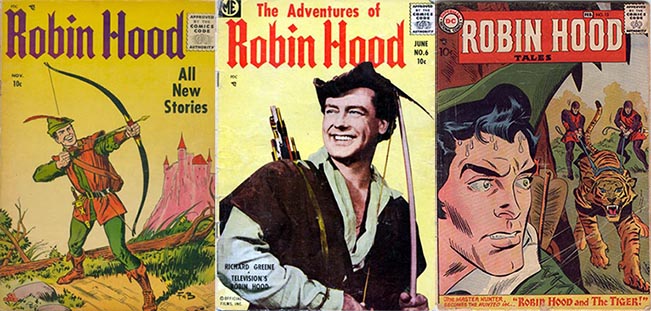

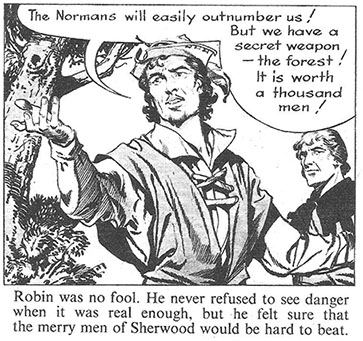

The 1950s were a boom period for Robin Hood comics. The 1952 Disney film The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men starring Richard Todd was adapted into comic book form in Dell's Four Color comic book series. and also in comic strip format Several publishers produced Robin Hood comics to cash in on the popularity of the 1955-1958 Richard Greene TV series, including an officially licensed comic from Magazine Enterprises and Robin Hood Tales from Quality Comics and later National (DC) Comics. Usually, the comic book Robin Hood of this era was clean-shaven with dark hair (like his then-current TV counterpart) and tended to have red, orange or yellow tunics rather than the familiar Lincoln green. Some of the hero's comic adventures were quite bizarre -- he faced off against tigers, hawks and apes. Once, the archer even donned a superhero disguise.

Also, Amalgamated Press published a series of Robin Hood annuals, which collected both colour and black-and-white Robin Hood comic book adventures. Oddly, the 1959 Annual features a story inspired by the Errol Flynn movie, complete with the likenesses of the actors, but also incorporating details which didn't make it to the final script. The annuals reprinted comic stories from issues of the Sun and Thriller Comics Library. It seems that the Flynn movie adaptation first appeared in Knockout comics from 1947, the year of the film's re-issue. These comics vanished by the time the Greene series went off the air. But there was another Robin Hood revival around the time of the Costner film. For example, DC Comics' 1991 Outlaws was set in an autocractic future where an outlaw named Lincoln Green took on the legacy of "Hood". And in the UK, both Robin of Sherwood and Maid Marian and Her Merry Men received short-lived comic book adaptations.

And Kermit the Frog has donned the bycocket cap once again in the comic book series Muppet Robin Hood. Issues 618 and 619 of the long-running Archie comic book series depicted the eternal teenager as the green-clad hero. A modern-day woman does some dimension-hopping heroics in Zenescope's Grimm's Fairy Tales: Robyn Hood series. In 2016 Robert Rodi and Jackie Lewis released Merry Men, a comic book series where Robin and his band are gay and fight the sexually repressive laws of the sheriff. Comic Book Heroes Inspired by Robin HoodAnd as a comic book fan, I feel compelled to mention superheroes that have been inspired by Robin Hood.

Green Arrow has often been a member of the Justice League of America, or JLA, a team that includes heroes such as Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman.

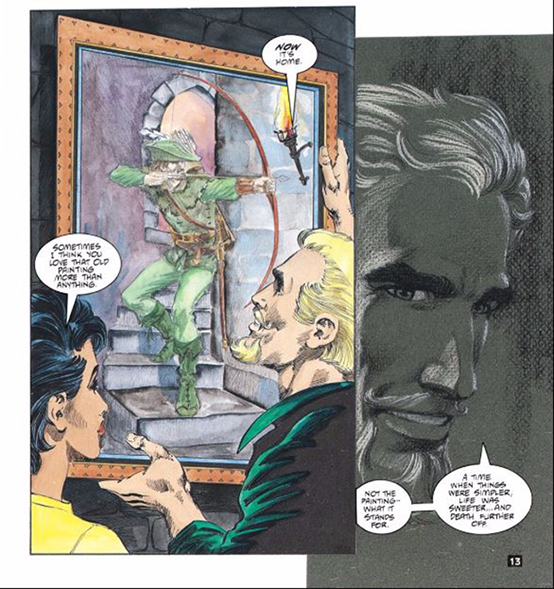

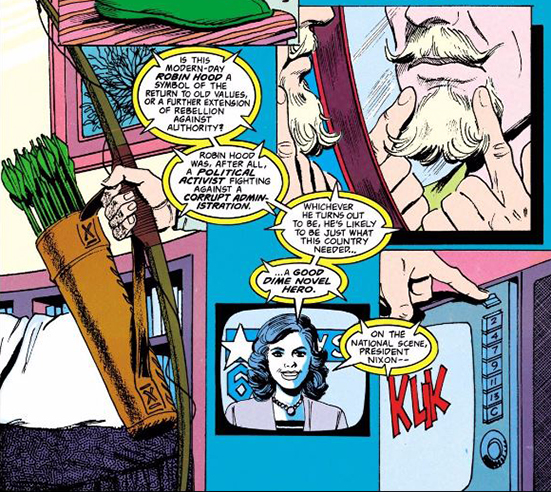

Thanks to the miracle of time travel and mystic (possibly drug induced) visions, Ollie has met his medieval inspiration on a few occasions. Robin of Sherwood actor Mark Ryan co-wrote a magical Robin Hood story where Green Arrow's girlfriend, the superheroine known as Black Canary, finds herself time-slipped into the body of Maid Marian. Mike Grell also drew illustrations for a version of Howard Pyle's children's book. His Robin Hood looks suspiciously like Oliver Queen. (Then again, when Ollie grew the goatee in the late 1960s, he looked a bit like Howard Pyle's Robin Hood.) Mike Grell's Oliver Queen is more political conservative than the younger version depicted by Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams. While the O'Neil and Adams Green Arrow looked towards Robin Hood as a figure of rebellion, Grell's version looks to Robin Hood as the representative of a lost golden age and traditional values.  As I mentioned back in the Ballads and Background section, modern Robin Hood scholarship began with the 1950s debate between Rodney Hilton and J.C. Holt over whether the medieval Robin Hood sought to overturn the social order or merely enforce traditional values. Grell touches on that debate in his retelling of Green Arrow's origin in 1989's Secret Origins #38 and 1993's Green Arrow: The Wonder Year #2. In both comics, a news anchor comments on Green Arrow's debut by comparing him to Robin Hood. "Is this modern-day Robin Hood a symbol of the return to old values or a further extention of rebellion against authority?"  Grell's Oliver Queen existed in his own continuty -- aging in real-time and free of the sci-fi trappings of most superhero comics. After Grell left the series, Green Arrow was re-incorporated into the regular "DC Universe", teaming up with a variety of heroes and villains from other comics. However, the character was now darker. It was not forgotten that under Mike Grell's run Oliver Queen killed some of his oppoonents -- which went against the censor-enforced moral code of most superheroes. For a time, Ollie was killed and replaced by his illegitimate son, Connor Hawke. But in 2001, Oliver Queen was resurrected in a new best-selling Green Arrow comic by movie writer/director Kevin Smith and artists Phil Hester and Ande Parks. Since Smith's departure, Green Arrow's adventures were written by best-selling novelist Brad Meltzer. Ollie continues to defend Star City, along with his son Connor and a new Speedy, Mia Dearden. Mia tested HIV positive - continuing Green Arrow's trend for dealing with social issues.  Oliver Green also spent some time as mayor of the fictional Star City, among his staff were Frederick Tuckman and John Smalls (Friar Tuck and Little John analogues). Ollie's political opponent was police commissioner Brian Nudocerdo (his surname is a combination of the Spanish words for knot and ham). Green Arrow has again been reshaped to resemble Robin Hood. When Ollie took the life of an enemy (a villain who, in true melodramatic fashion, had destroyed much of Star City, maimed Ollie's former sidekick and killed Ollie's grandaughter), he was exiled from Star City and now operates from a magical forest which has appeared in ruined section of the city. The original Speedy started using the name Arsenal. After serving on various versions of the Teen Titans, Roy changed his alias to Red Arrow and took his mentor's place in the Justice League. After losing both his arm and granddaughter (see above), Roy returned to the Arsenal name and fell into a more criminal existence. In 2011, DC Comics revamped their line of comics again, eliminating most of Green Arrow's history but publishing new Green Arrow comics. In 2016, DC Comics launched its Rebirth set of titles. Although following the 2011 continuity, previous elements of Green Arrow's history were re-introduced by writer Benjamin Percy and various artists. Oliver Queen grew his signature goatee, fell in love with Black Canary again and lost his fortune yet again.  The hero was a supporting character in the Smallville TV series, and as of 2012 is the title character of the CW TV series Arrow. In Arrow, Oliver Queen is assisted by a team of heroes -- some adapted from the comics and some created for the series. TV series character John Diggle (played by David Ramsey) has been incorporated back into the comics. This is similar to how Maid Marian and Friar Tuck may have entered the Robin Hood ballads through their appearances in plays.

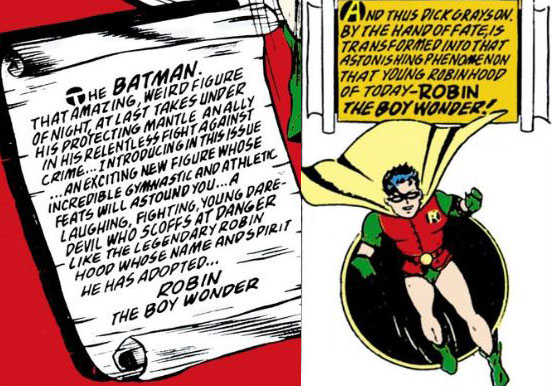

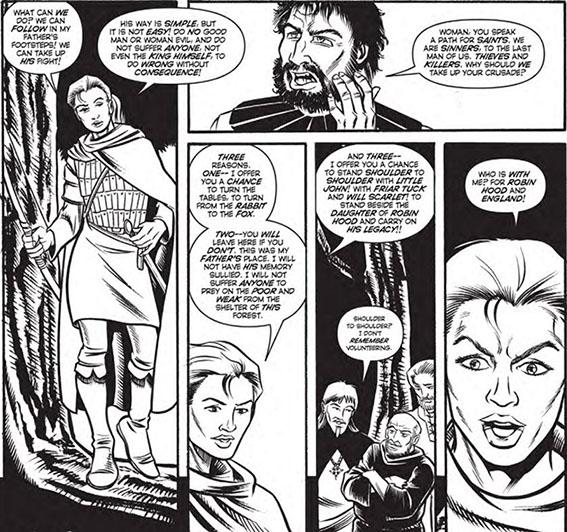

There are have been many other comic book bowmen. Marvel Comics has their own archer, Hawkeye. The purple-clad Hawkeye aka Clint Barton started as an outlaw but quickly reformed to become a brash member of the superhero team, the Avengers. Briefly, he returned to his Robin Hood roots by becoming leader of the villains turned heroes called the Thunderbolts. Clint was obviously inspired by Green Arrow and used trick arrows. On the other hand, Green Arrow might have borrowed Hawkeye's pain-the-butt attitude.  But the most popular comic book character based off Robin Hood doesn't carry a bow. He's Robin the Boy Wonder, Batman's long-running sidekick. In his early appearances in 1940 Robin is described as "that young, laughing Robin Hood of today." It is clear from those stories that he takes him name from Robin Hood as much as the robin redbreast. Two of the Robins [several kids have assumed that identity; the original -- Dick Grayson -- now goes by the name Nightwing] have used the archaic sling, and in some stories Tim Drake, the 1990s Robin, uses a staff like Robin Hood does in some later ballads. Robin co-creator Jerry Robinson notes that Robin's costume was also based on that of the famous outlaw, specifically the classic illustrations of N.C. Wyeth. Robin Hood-inspired heroes continue to appear in comics. In 1998, Caliber Comics started publishing Robyn of Sherwood. The title character was the daughter of Robin Hood and Maid Marian and she's reformed the Merry Men to fight King John. The writer of this series, Paul Storrie, also wrote a classic Robin Hood adventure in 2001's Robin Hood and the Minstrel. In 2007, Pauk Storrie and Thmas Yeates released Robin Hood: Outlaw of Sherwood Forest, a retelling of the legend in a Classics Illustrated style. In 2012, Robyn of Sherwood was released in a collected edition with new art by Rob Davis.  Fictional and Real People Inspired by Robin Hood

As discussed in the previous section, Robin Hood has often been reworked into a science fiction setting such as the Rocket Robin Hood cartoon. The crooks/freedom fighters of the British sci-fi series Blake's 7 have a certain Robin Hood vibe about them. Even more Robin Hood in nature was the cult classic series Firefly (and follow-up movie Serenity created by Joss Whedon (of Buffy the Vampire Slayer fame). The heroes of that show were a colourful band of smugglers who didn't have the coziest relationship with authority. There was even a preacher with a suspicious past among these interstellar Merry Men. While mostly concerned with putting food on their tables, Captain Mal Reynolds and the crew of Serenity did help the common people on occasion.

Firefly was also a homage to the classic westerns. And while the wild west may look quite different from the verdant forest of Sherwood, the frontier spirit of westerns is a good fit for the Robin Hood legend. Roy Rogers starred in Robin Hood of the Pecos and The Trail of Robin Hood. Fellow cowboy Gene Autry played the lead in Robin Hood of Texas. Robin Hood comparisons are not restricted to fictional characters. Real-life outlaws Billy the Kid and Jesse James have been compared to Robin Hood as their criminal activities were romanticized. And even political types have been associated with the hero in lincoln green. Phoolan Devi, the late Bandit Queen of India, has often been called a Robin Hood figure, and she eventually became a politician. Left-wing activist and filmmaker Michael Moore has been compared to Robin Hood, but then so has Joerg Haider, the far right-wing Austrian politician. In Canada, fringe mayoral candidate the late Tooker Gomberg dressed in a Robin Hood costume and used his toy bow to challenge the then-current mayor of Toronto on the issue of poverty. Of course, there are other comparisons to the legend that one can make. In November 2005, European Commissioner Jose Manuel Barroso mentioned the Robin Hood legend and said that he didn't want UK Prime Minister Tony Blair to take the role of the Sheriff of Nottingham by limiting funds to poorer EU countries. It shows how diverse the Robin Hood legend has become that it can be reflected in superheroes, sci-fi smugglers, cowboys, freedom fighters and even politicians. Now, back to the original heroic archer.... NEXT: Robin Hood in the Present and the Future Green

Arrow is copyrighted to DC Comics and the images are used without permission

for purposes of review and criticism. The artists were Neal Adams and Mike

Grell. Frank Bellamy's art comes from the 2008 Book Palace collected edition of the 1950s comic, Frank Bellamy's Robin Hood: The Complete Adventures, and is likewise used without permission for the purposes of criticism and review. Sources and Further Reading: Click here to view additional information sources used for this specific section. Text copyright, © Allen W. Wright, 1997 - 2013. |

|

|

Meanwhile

in Great Britain, publishers such as World, Miller and Streamline/United Anglo-American reprinted the American Robin Hood comics of the 1950s. TV Heroes had a Robin Hood comic feature. And Pearson's TV Picture Stories adapted three Richard Greene stories into comic book form. One of the greatest British comic book artists - Frank Bellamy - also drew

Meanwhile

in Great Britain, publishers such as World, Miller and Streamline/United Anglo-American reprinted the American Robin Hood comics of the 1950s. TV Heroes had a Robin Hood comic feature. And Pearson's TV Picture Stories adapted three Richard Greene stories into comic book form. One of the greatest British comic book artists - Frank Bellamy - also drew  And it seems Robin Hood's return to 21st century television has sparked several new comic book projects. Among the first to appear is an online comic,

And it seems Robin Hood's return to 21st century television has sparked several new comic book projects. Among the first to appear is an online comic,  Chief

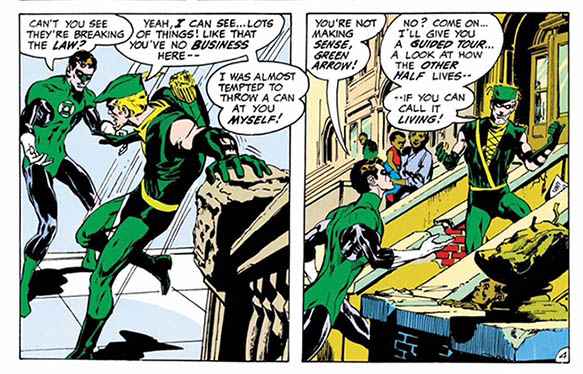

among these is DC Comics' classic Green Arrow. He was Oliver Queen, a millionaire

playboy -- a Batman with a Robin Hood motif. Instead of a utility belt,

he had trick arrows -- my personal favourite being the boxing-glove arrow

(yes, an arrow with a boxing glove stuck on the end of it). And he had a sidekick, a red-clad "bow bowman" named Speedy (aka Roy Harper). Green Arrow first appeared in More Fun Comics #73 in 1941, and his adventures ran for decades as a supporting feature in World's Finest Comics and Adventure Comics. For the most part, the early version of Green Arrow only resemembled Robin Hood in terms of costume and gimmicks. But in 1969, artist Neal Adams would revamp the character's look and writer Denny O'Neil would revamp his personality. (

Chief

among these is DC Comics' classic Green Arrow. He was Oliver Queen, a millionaire

playboy -- a Batman with a Robin Hood motif. Instead of a utility belt,

he had trick arrows -- my personal favourite being the boxing-glove arrow

(yes, an arrow with a boxing glove stuck on the end of it). And he had a sidekick, a red-clad "bow bowman" named Speedy (aka Roy Harper). Green Arrow first appeared in More Fun Comics #73 in 1941, and his adventures ran for decades as a supporting feature in World's Finest Comics and Adventure Comics. For the most part, the early version of Green Arrow only resemembled Robin Hood in terms of costume and gimmicks. But in 1969, artist Neal Adams would revamp the character's look and writer Denny O'Neil would revamp his personality. ( In

the late 1960s and early 1970s, he lost his fortune (to man named John

Deleon, a name suggesting Prince John), grew a goatee, and became an angry,

spicy chili-loving, outspoken defender of the downtrodden in a series of

"socially relevant" comic books with help from fellow superhero Green Lantern.

These classic issues were written by Dennis (Denny) O'Neil and drawn by

In

the late 1960s and early 1970s, he lost his fortune (to man named John

Deleon, a name suggesting Prince John), grew a goatee, and became an angry,

spicy chili-loving, outspoken defender of the downtrodden in a series of

"socially relevant" comic books with help from fellow superhero Green Lantern.

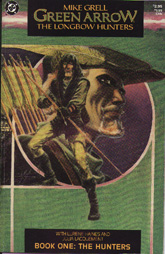

These classic issues were written by Dennis (Denny) O'Neil and drawn by In the late 1980s and early 1990s, writer/artist Mike Grell remade Ollie in a mini-series called "The Longbow Hunters". Grell wrote the regular Green Arrow series that followed. Ollie aged into his forties, moved to Seattle, ditched the

trick arrows in favour of your standard pointed type and fought street crime. Grell is fan of the Robin Hood legend and his run contains many allusions to the legend, including such things as Ollie singing the 1950s TV show theme as he practices archery. Also, it established that Oliver Queen learned archery from Howard Hill, the real-life archer who advised the 1938 Errol Flynn film. (Robin Hood themes also loomed large in the flashback 2007 comic book mini-series Green Arrow: Year One by Andy Diggle and Jock.)

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, writer/artist Mike Grell remade Ollie in a mini-series called "The Longbow Hunters". Grell wrote the regular Green Arrow series that followed. Ollie aged into his forties, moved to Seattle, ditched the

trick arrows in favour of your standard pointed type and fought street crime. Grell is fan of the Robin Hood legend and his run contains many allusions to the legend, including such things as Ollie singing the 1950s TV show theme as he practices archery. Also, it established that Oliver Queen learned archery from Howard Hill, the real-life archer who advised the 1938 Errol Flynn film. (Robin Hood themes also loomed large in the flashback 2007 comic book mini-series Green Arrow: Year One by Andy Diggle and Jock.)

But it's not just comic books that have created heroes based off Robin Hood.

Zorro, Simon Templar (aka the Saint), and even the Dukes of Hazzard have

been called modern-day Robin Hoods. The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

has a few Robin Hood parallels, most notably Faramir and his rangers of Gondor.

In the film version of The Two Towers, director Peter Jackson shows an ambush

by Faramir's (David Wenham) archers that seems straight out of an N.C. Wyeth

illustration or a Robin of Sherwood episode. But it's Orlando Bloom as the

elf Legolas who performed the most crowd-pleasing feats of archery.

But it's not just comic books that have created heroes based off Robin Hood.

Zorro, Simon Templar (aka the Saint), and even the Dukes of Hazzard have

been called modern-day Robin Hoods. The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

has a few Robin Hood parallels, most notably Faramir and his rangers of Gondor.

In the film version of The Two Towers, director Peter Jackson shows an ambush

by Faramir's (David Wenham) archers that seems straight out of an N.C. Wyeth

illustration or a Robin of Sherwood episode. But it's Orlando Bloom as the

elf Legolas who performed the most crowd-pleasing feats of archery. The episode "Jaynestown" (written by Ben Edlund) is a clear homage to the Robin Hood legend. Years before, Jayne, the most amoral Firefly character, robbed the local magistrate of a mud-farming town. Jayne's shuttle was damaged, and he had to unload this stolen loot to keep his ship in the air. The money landed on the poor mudfarmers -- and they took Jayne for a Robin Hood hero. They even crafted a ballad with the lyrics "He robbed from the rich/ And he gave to the poor./ Stood up to the man and gave him what for."

The episode "Jaynestown" (written by Ben Edlund) is a clear homage to the Robin Hood legend. Years before, Jayne, the most amoral Firefly character, robbed the local magistrate of a mud-farming town. Jayne's shuttle was damaged, and he had to unload this stolen loot to keep his ship in the air. The money landed on the poor mudfarmers -- and they took Jayne for a Robin Hood hero. They even crafted a ballad with the lyrics "He robbed from the rich/ And he gave to the poor./ Stood up to the man and gave him what for."