Introduction

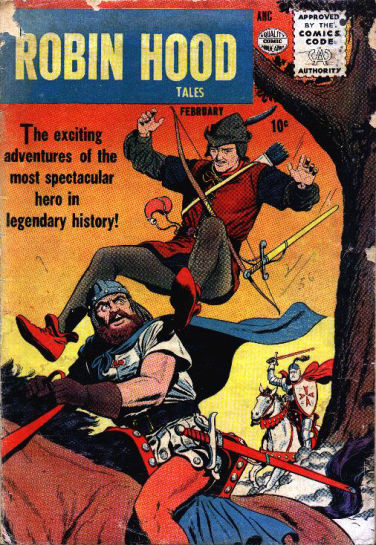

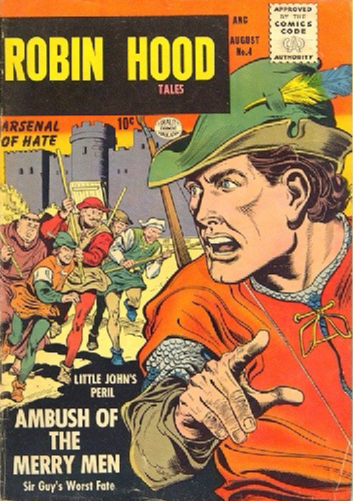

Quality Comics, 1956

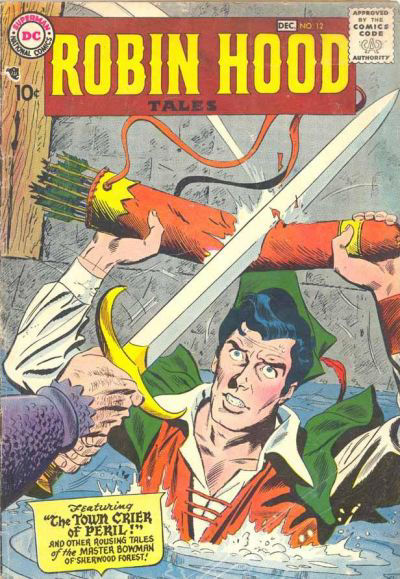

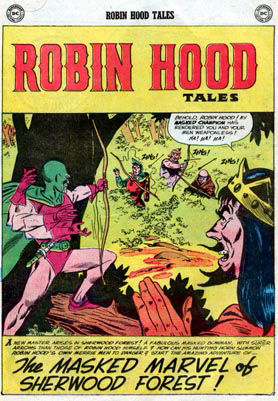

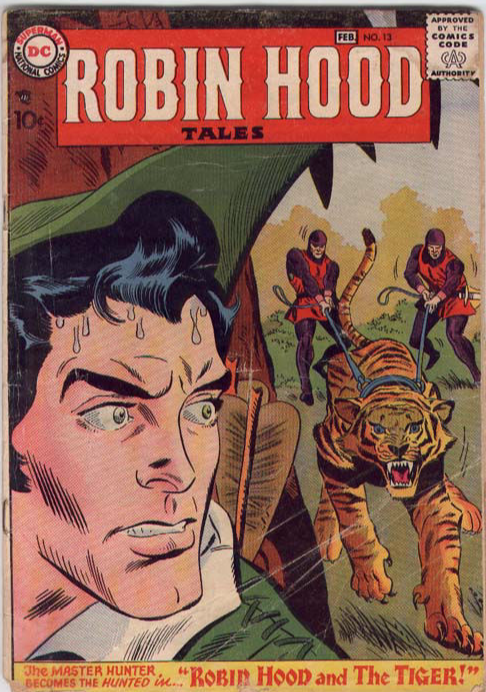

National (DC) Comics, 1957-1958

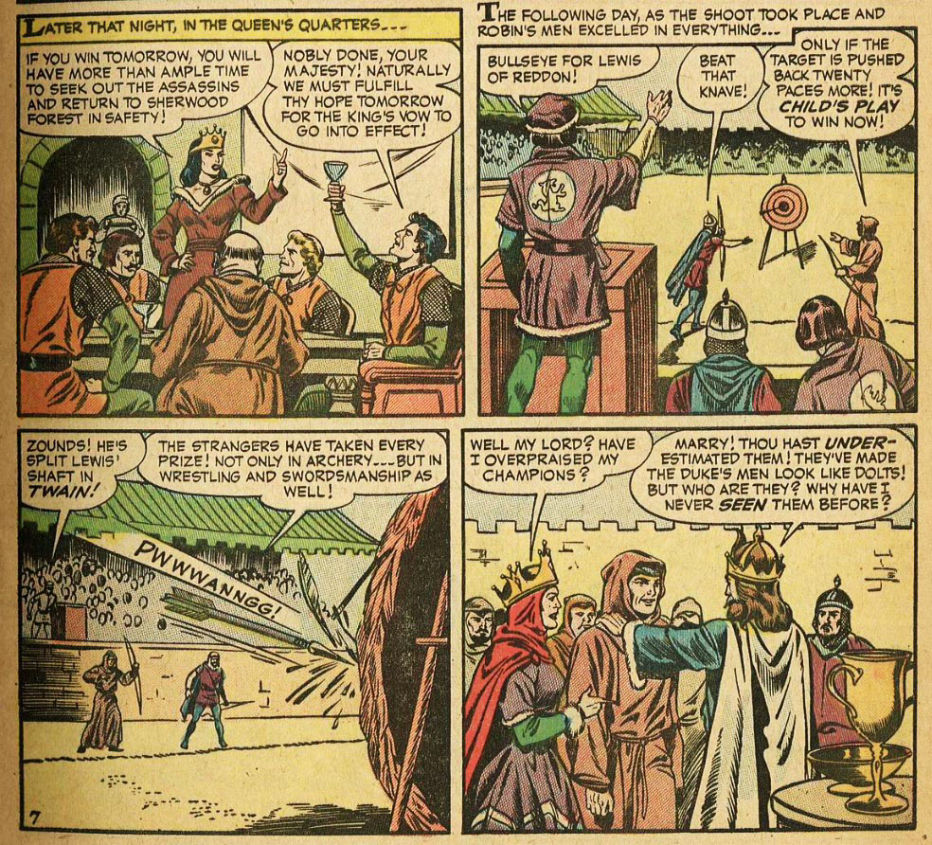

I've been a fan of comic books since my childhood. I've also been a fan of Robin Hood since my youth. But until recently (well, recently when this was first written over 20 years ago), I've never collected Robin Hood comics.

Then, in March of 1998, the call went out for papers for the SouthEastern Medieval Association's annual conference. A friend on the Robin Hood mailing list wanted to do a Robin Hood roundtable. I submitted two ideas, and she picked the one about Robin Hood comic books of the 1950s. The conference approved our plan.

Trouble was, aside from the reprint of one 8-page story, I didn't have any 1950s Robin Hood comics. So, I went shopping.

In a column in Comic Book Marketplace, Michelle Nolan notes that at least 7 publishers produced Robin Hood comics during the years of the classic Richard Greene TV series. Like Nolan, my favourites were the ones produced by National (better known as DC) Comics.

Contact Us