The Writers and the Sunday Tea-Time Serial

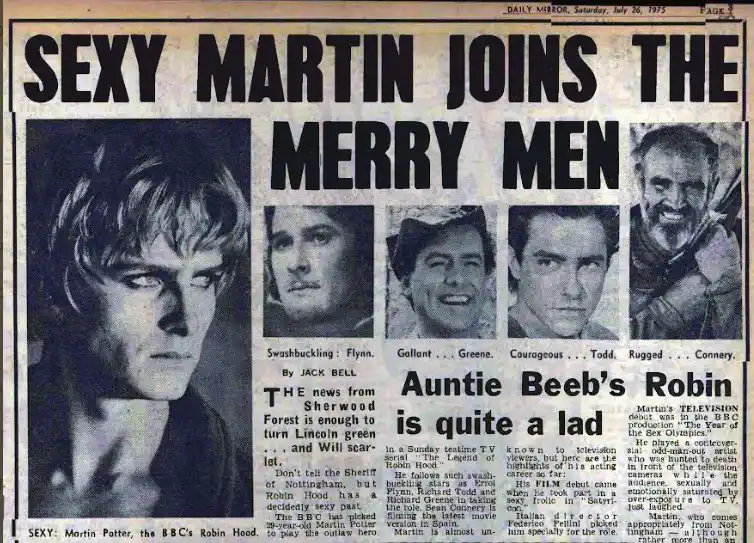

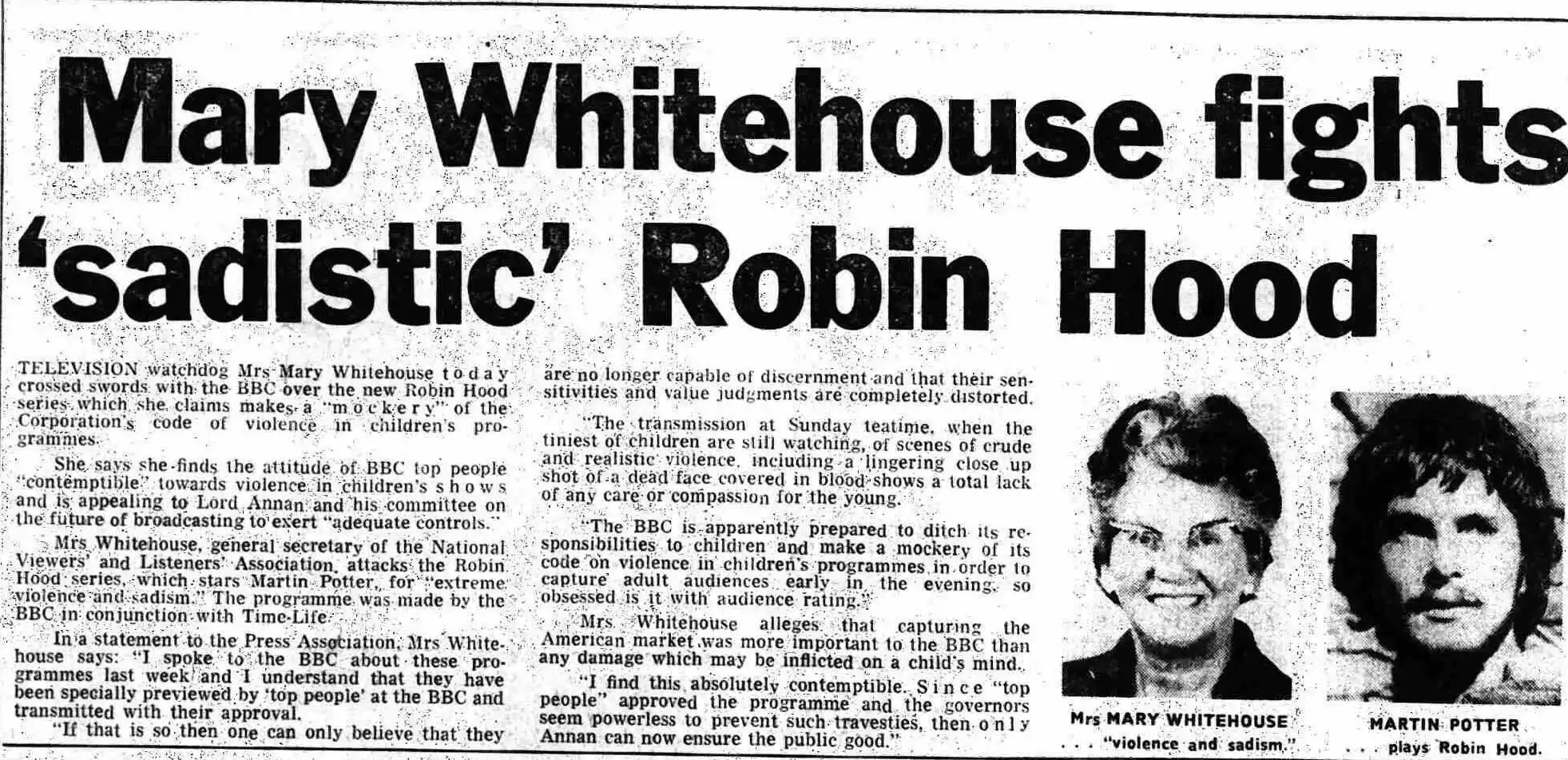

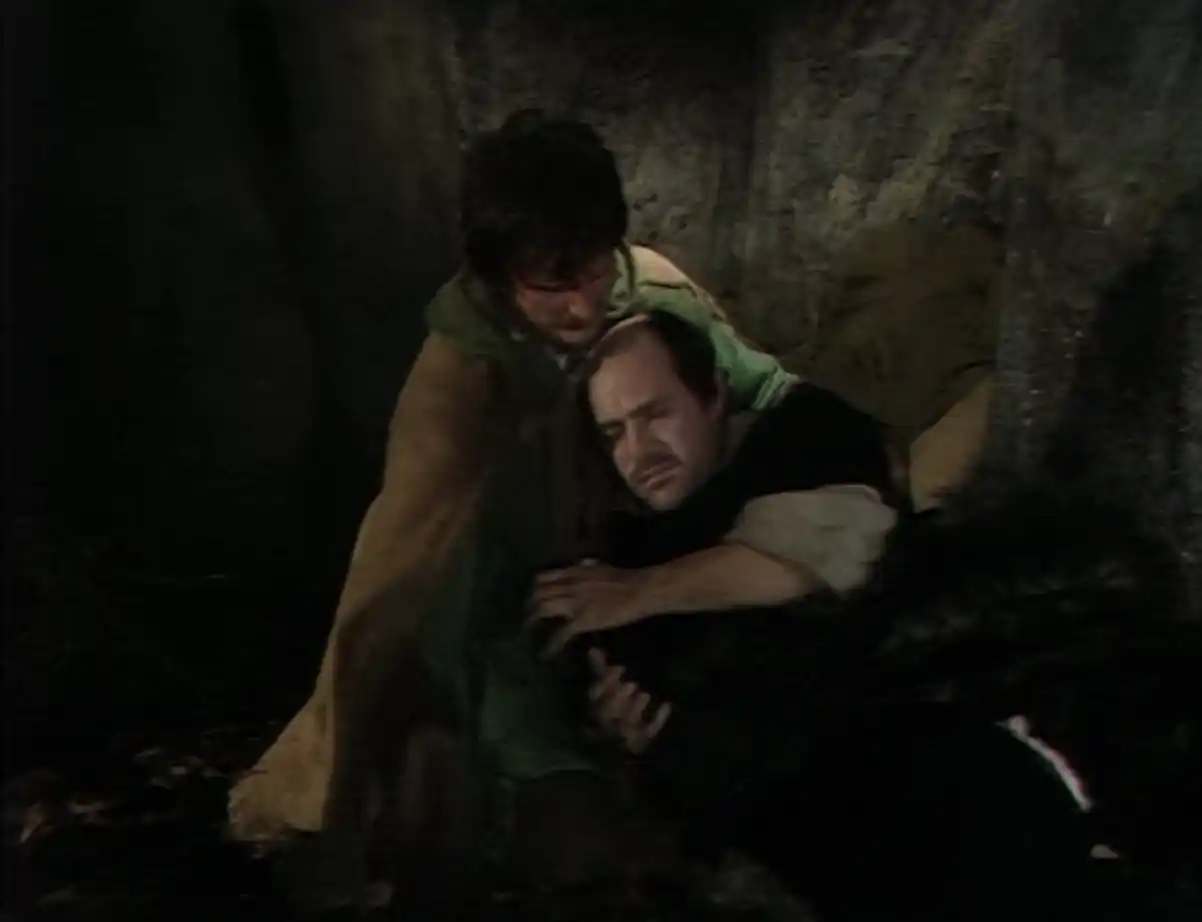

The Legend of Robin Hood was produced to be one of the BBC’s Sunday tea time serials. These shows were historical and literary adaptations— often praised for the quality of the writing. The BBC’s accountants might also have praised them for their low budgets -- even if few actual viewers did.

The person most directly responsible for the quality of the writing would be Alistair Bell who wrote the first episode, co-wrote the final episode and served as script editor for the whole series — adjusting the scripts of others. By 1975 Bell already had an impressive TV pedigree especially at tea-time. He wrote the well-regarded 1970 adaptation of Little Women and the 1973 TV series Hawkeye, the Pathfinder. The Hawkeye series was a sequel to 1971’s The Last of the Mohicans for which Bell had served as script editor. He was script editor on serials such as The Elusive Pimpernel (1969), Anne of Green Gables (1972), Jane Eyre (1973), David Copperfield (1974) and The Master of Ballantrae (1975) to name just a handful.

Robert Banks Stewart wrote the second and third episodes and co-wrote the final episode with Bell. He also has a lengthy TV resume, although not so much with the classic serials. At the time, his name would be most associated with the adventure shows aired on the Independent Television channels - classics such as The Avengers, The Saint, The Protectors and five episodes of their gritty, less romanticized Arthurian series Arthur of the Britons. Viewers of the BBC would most recently have associated him with the creation of the Zygons on Doctor Who, and shortly after the conclusion of The Legend of Robin Hood, Stewart would contribute the Krynoids to the Doctor's rogues gallery.

The fourth episode is written by actor-turned-writer David Butler, who has a good claim for being the person to initiate the modern, more realistic cinematic Robin Hood. He both wrote and appeared in (as friendly forester Will Stukely) the largely forgotten but still influential TV pilot (later released as a B-movie) Wolfshead: The Legend of Robin Hood. Butler's earlier project drew heavily from the medieval ballads and his episode of this show adapts the late medieval ballad A Gest of Robyn Hode.

The fifth episode is credited to Alexander Barron, although the writer born Joseph Alexander Bernstein generally spelled his pseudonym Alexander Baron -- with a single R in the surname. Baron's World War II-era novels had some acclaim, and he already had Sunday tea-time experience as the writer of the 1970 TV adaptation of Ivanhoe, script-edited by Alistair Bell. He would go on to write more literary adaptations after his time with Robin Hood including the 1982 The Hound of the Baskervilles starring Tom Baker and the 1984 TV episode "A Scandal in Bohemia", the debut episode of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes starring Jeremy Brett.

Contact Us