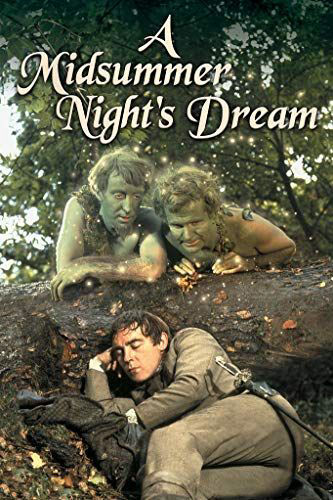

A Dream Cast

The 1968 film version included some of the finest actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company. In addition to the actors carried over from the previous stage versions, David Warner (perhaps the definitive Hamlet of the 1960s) joined as Lysander, Michael Jayston (previously Laertes to Warner’s Hamlet) is Demetrius, Paul Rogers (who played Max in Pinter’s The Homecoming) is Bottom, and a young Helen Mirren is Hermia.

At the time, American audiences would have been most familiar with Diana Rigg who in between her stage and film roles as Helena had become an international sensation as Emma Peel in the adventure TV series The Avengers.

And yet, even people born a quarter century after this film was shot would now recognize much of the cast. Viewers who don’t know Rigg for her iconic Avengers role might remember her as the scheming Olenna Tyrell in HBO’s Game of Thrones.

Ian Richardson delighted TV audiences as the almost Shakespearean villain Francis Urquhart in the original British TV version of House of Cards (available on Netflix along with its modern American remake). David Warner is a welcome presence in any number of TV shows and movies (including 1997’s Titanic and two Star Trek movies). Ian Holm appeared in 1979’s Alien – a film with a long shelf life. And younger generations would know him as the older Bilbo Baggins in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit film trilogies. Judi Dench and Helen Mirren are screen icons from many beloved movies and TV shows.

But their later successful film and TV careers is mere coincidence. At the time, these were some of the finest stage actors the Royal Shakespeare Company had to offer the world. When Peter Hall re-birthed Stratford’s theatre as the RSC, he brought along John Barton to improve the way actors spoke Shakespeare. Barton and Hall played very close attention to text, and their actors spoke the words “trippingly on the tongue” (to quote Hamlet’s advice to the Player King) in a way that would be understandable and clear to modern audiences without be jarringly modern.

There would be no Warner Brothers studio players struggling with the text as there had been in the 1935 version of the Dream.

Instead, the struggles came from crawling around in the undergrowth of the location film. It was noisy and most of the dialogue was re-recorded in the studio afterwards. As Hall himself remarks in his autobiography, “As a consequence, it is a beautifully spoken Dream.”

">

">

Contact Us