A Hollywood Dream

The 1990s were a good decade for Shakespeare on screen. Kenneth Branagh earned critical acclaim with his 1989 adaptation of Henry V and followed that up with well-regarded versions of Much Ado About Nothing (1993) and Hamlet (1996). If not as critically acclaimed as Branagh’s melancholy Dane, action film star Mel Gibson’s 1990 turn as Hamlet also did well at the box office. And Baz Luhrmann’s modern take on Romeo + Juliet (1996) with star Leonardo DiCaprio made over 10 times its budget. No wonder that William Shakespeare’s name appeared so prominently in the title, that guy was good for business.

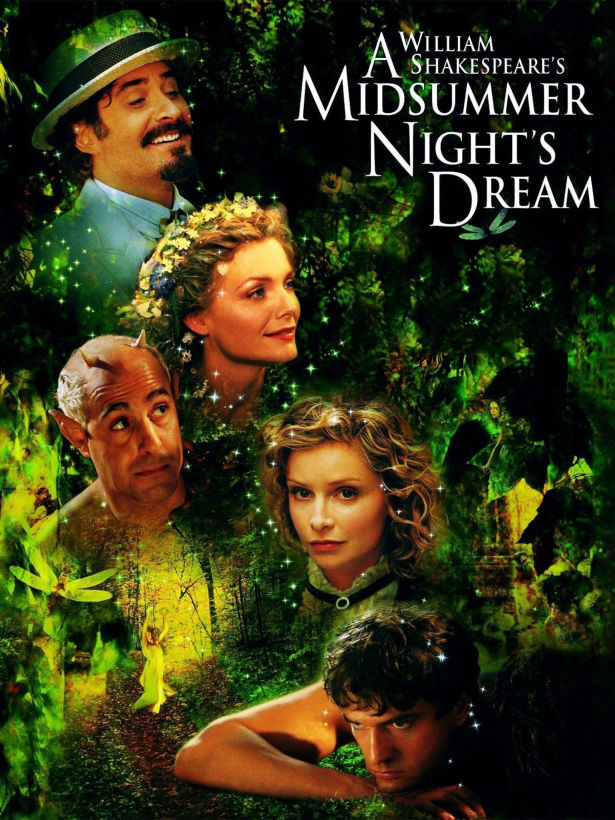

Like its 1935 predecessor, this version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream features a galaxy of bankable box office stars. But the 1935 Dream and many of the subsequent film adaptations had started life as a stage production. This Dream was a creature of the movies alone.

">

">

Contact Us