A Bold Rascal

The Robin Hood legend has fascinated me for as long as I can remember. It's easy to explain why I like some versions and why I don't like other versions. It's a little harder to explain why I love the legend as a whole.

What Robin Hood stands for can change radically. The character can be a left-wing redistributor of wealth or a right-wing tax-fighter. Robin can be a nationalist or an environmentalist. The flexibility of the Robin Hood legend is its greatest strength. And yet, the legend would not last as long as it has if the character was a mere cipher.

The story of Robin Hood is not just a vessel for a political or social agenda. It is a story with drama, action, humour and all the other elements that allow good tales to last.

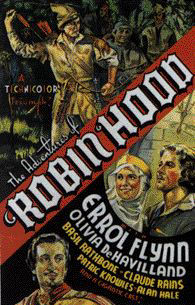

Perhaps Prince John says it best in the Errol Flynn film, "By my faith, but you're a bold rascal. Robin, I like you." Even though the Robin Hood legend has changed greatly over time, there is a sense of boldness in the best Robin Hoods. I think whether we're children in the schoolyard or stuck in a cubicle, there are times when we want to speak out and we can't. Robin Hood can and does. His defiance and outlaw freedom appeals to anyone who feels frustrated or inhibited.

And in the best Robin Hoods, there's a sense of the trickster about him. Robin doesn't just fight his enemies with arrows and swords. He mocks them. In some ways, Robin's wit makes him seem more rebellious and defiant than any physical weapon ever could.

And though it's role in the early legend is murky at best, I would not want tob be like certain newspaper writers and leave out Robin Hood's sense of charity and helping the underdog. Sometimes he'd just flout authority but other times Robin Hood helps those in distress. That's not a bad thing.

Time and again, I reflect upon a scene between Robin Hood and Maid Marian in the 1938 movie. Robin and Marian have left the grand banquet in Sherwood as Robin helps those suffering the most from hunger.

Contact Us