Butchers, Highwaymen and Robin Hood

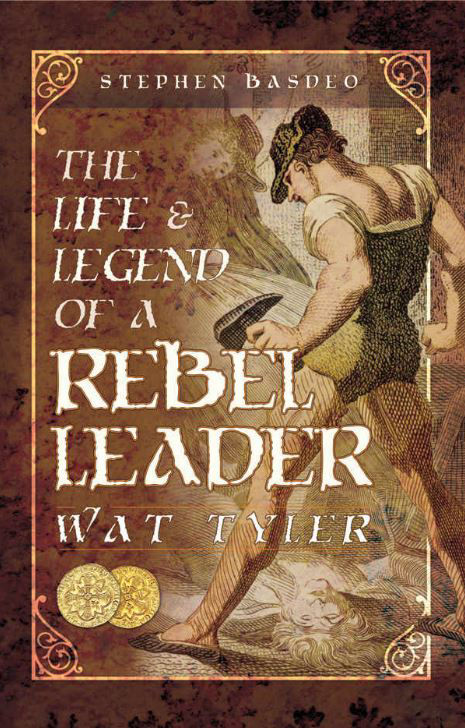

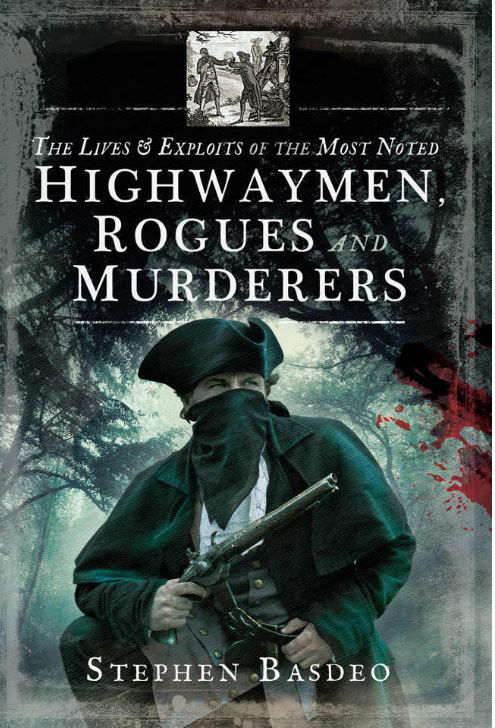

AWW: In your book on The Lives & Exploits of the Most Noted Highwaymen, Rogues and Murderers, you mentioned how figures like Captain James Hind, Dick Turpin and Jack Sheppard were all depicted as being butchers at some point in their career. I thought about the Robin Hood ballad where he assumes a butcher's disguise, but I was surprised to learn in your book Robin Hood: The Life & Legend of an Outlaw that in Alexander Smith's 18th century history of highwaymen that Robin Hood himself was raised as a butcher. What is the reason for this literary connection between being a butcher and a robber?

SB: I guess I should signal that I’ve recently written a chapter on the connection between highwaymen and butchering in a recent edited collection by our mutual friend, Alex Kaufman (and so fulfil my contractual obligation with Routledge to promote the book in general…), entitled Food and Feast in Modern Outlaw Tales (2018).

In Alexander Smith’s History of the Highwaymen and Charles Johnson’s Lives and Exploits of the Most Noted Highwaymen—you can see from those titles the tradition in which I was trying to situate my own book—Robin Hood is indeed depicted as a butcher. The first thing to note is that Robin Hood in these books is not a ‘medieval’ figure by any stretch; the accounts are de-historicised and Robin Hood is, to all intents and purposes, an seventeenth/eighteenth-century highwayman.

In real-life terms, eighteenth-century butchers were, surprisingly, often well-connected with members of the criminal underworld. Meat, and good meat, was an expensive commodity in the eighteenth century. Draconian laws against poaching on private lands, some of which originated in the time of our hero, Robin Hood, were still in place. Added to this were new bylaws (laws established in a particular parish or town which do not require an Act of Parliament) banning poaching from specific places, where the medieval laws had only dealt with the Royal forests and parks for the most part. In spite of this the crime of poaching remained endemic; poachers, of course, needed somewhere to dispose of their stolen meat, so butchers acted like receivers of stolen goods in meat, acquiring stock at a cut price and undercutting their fellow butchers. And the butchers were only too ready to do this; competition in the marketplace, for the medieval butchers’ guilds were largely an irrelevance by this point, led to butchers being more willing to engage in criminal activity. Some butchers decided to cut out middle men and just go poaching themselves, and from there they usually became involved in gangs after which they became wanted men. In short, the meat trade was an easy route into a criminal life (though we mustn’t overplay this all the same, for while many highwaymen were butchers, there were of course a number of respectable butchers who never turned to crime in the eighteenth century, and many other trades are represented in the annals of the highwaymen.

Yet because butchering is an unpleasant trade, in cultural terms, a number of other fears regarding the alleged brutality of the trade and, by extension, the moral character of butchers at large also developed. John Gay, who wrote The Beggar’s Opera (1728), also wrote a few words which neatly illustrate the public view of butchers:

Butchers, whose hands are dy’d with blood’s foul stain,

And always foremost in the hangman’s train.

The implication was that, if a person was willing to kill a defenceless animal—and the Georgians recognised that animal cruelty went hand-in-hand with criminality (see Hogarth’s Industry and Idleness)—then a person probably had very few qualms about harming other people. Now, not every highwayman/butcher in Smith’s work was probably in real life a butcher—Smith probably just made up that ‘fact’ for half of them—but the material circumstances of daily life, the people who they came into contact with, and the negative connotations with the trade made butchers a convenient scapegoat for criminality.

Contact Us