The

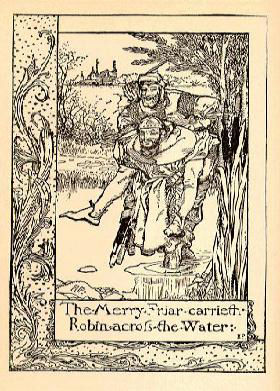

Sunday Times story boiled this down to Was Robin Hood Gay ? There was

a fine colour pic of ultra-handsome Errol Flynn and an astutely selected

illustration by Howard Pyle, the very influential American illustrator of

1883, showing Robin and Friar Tuck playing horsey in the water. The text

focused on the sharp shock of the gay charge, but also, as suits a serious

Sunday paper, had research on show: the distinguished Barrie Dobson, Professor

at Cambridge, said that homosexuality in the medieval period was not necessarily

as repressed as you might think, and there was a nice round-up from the present

Earl of Huntingdon saying goodness gracious me.

As

I had expected there was fall-out. My wife trained as a journalist on a

Rupert Murdoch paper in Australia, and we have some experience of how a new

story can suddenly start a media feeding frenzy, but this was bigger than

both of us. I got back from my tour-preparing trip on a Sunday to find that

a few wily journalists had got my number from security at my university.

I wonder what they think security means. First up were the BBC, awake to

the world as ever. One call was from Radio 5, the brainless lightweight morning

chat show; the other from Radio 4's Today that voice of managerial Britain.

I explained to both about the beat-up element, plus my view that there is

a credible gay reading of the tradition, and that this is one of the reasons

for its continuing popularity: the politics of the outlaw can be gay as much

as socialist, nationalist, internationally liberal, tricksterish whatever.

`Sounds great' said chatty Gina from Radio 5; `what about five minutes tomorrow

morning ?' It was a brief, slightly breathy, but well-managed interview. Radio

4 Today was different - and not in my view to its credit. The obviously highly

intelligent, no doubt Oxbridge-trained producer, was looking for a shock

`RH was gay' story. I gave my temperature-reducing spiel. `Oh,' she said,

`we'll have to think about that. I wonder how we could focus that.' `Don't

worry,' I replied, `never mind,' concealing my dislike of those measured morning

tones that monitor and mentor the world. They never called back. Why did

schlock radio not mind my diluted, more thoughtful story, and the alleged

higher echelons shy away from my lack of vulgar focus ? Robin Hood's sexuality

is not the only tender spot in this developing saga.

In

the next few days at work the phones were hot, and the secretaries bothered.

I did a startling number of radio interviews, probably thirty in the week.

Memorable were a couple of debates with the folks from Nottingham, more

put out than usual, and feeling very threatened by the whole idea of unnatural

forest practices; and even surlier when, perhaps now getting silly, I suggested

they should chase the pink dollar like Sydney with its Gay Mardi Gras. The

reflex of Nottingham offence was the substantial number of local radio interviews

with towns neighbouring on and so hostile to the outlaw Jerusalem: Sheffield,

Leicester, Northampton, Birmingham were all delighted to speculate on Robin

Hood's high jinks and the resultant glum visages in what the Anglo-Saxons

called Snottingham.

But

it went further afield than that. As before when I have published new and

slightly wacky ideas on topics like crime fiction, outlaws, gender and politics,

the big countries with serious nationally interlinking radio came to the party.

Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia were on the phone early and

I did some lengthy and thoughtful interviews with them, though we got off

to a bad start with the guys from Radio Winnipeg who wanted to know if Cardiff

University was in London. `It's not even in England' I said, haughtily Welsh,

but they were highly cheerful and very amusing so things turned out fine.

These were fairly standard interviews, starting with a mock-shock introduction,

then responding with some interest and drawing out questions when I ran my

spiel about a media beat-up and a genuine gay interpretation of the tradition.

But Australia, where I lived for years, and where our children were born,

was as usual as different as a kangaroo's pouch. One interview, with Melbourne

ABC, was very long and thoughtful - a solid fifteen minutes or more. The

other was a hysterical short with an over-hyped Sydney DJ, witty and cheerful

to the limit, who seemed to have a roomful of hysterics as an immediate audience.

New

territory to me, and a bit unfathomable, were the interviews with English-capable

Europe: Germany (three stations), Norway (two), Holland and Sweden all recorded

medium length interviews, with some off the wall questions like the remorselessly

well-educated Teutonic curve ball `What generically speaking do you think

is the crucial focus of the outlaw tradition ?' I was able to gulp `Drama'

and gather myself for a more measured response.

I

did no television at all, in spite of quite a lot of requests. It wasn't

hard to turn down an invitation to appear as the daft prof on the Graham

Norton show and The Big Breakfast, but my painful experience is that TV on

any topic takes ages, gets nowhere, and both fetishises and disempowers you

and your arguments. I don't understand why, but I have always found it a

total waste of time, even on Robin Hood. The assistants are always puzzled

then hurt and finally rude, but I still say no. Print and radio seem plenty

and there the sheriffs are more friendly.

No

interviewer in all this was hostile to the idea of Robin Hood being gay,

though most suggested that presumably some people would take that negative

position. Few of them knew anything much about the myth, though most asked

a few leading questions, mostly based on the Robin and Marian interaction

through time. A few were in it for a laugh (or as in Sydney a scream) but

most were professionally competent, letting the story run, at least for a

while. The most serious of the interviews were with people who had a gay

orientation. The Chicago Lesbi-Gay line (if I spell that right) were both

highly professional about timing and ringing beforehand to remind me, and

also in a high-spirited way intelligent about the whole notion of reading

a tradition for its sub-texts and potential social meaning; if they were

late-night elevated, a Miami line was quiet toned and deeply thoughtful,

pursuing an entirely original interest in the ballads as poetry - deep waters,

but worth exploring. And perhaps in this category comes the most curious

and satisfying of all the interviews, one with the British Forces Network

(I had no idea we still had this ancient instrument of military imperialism).

Two men called Guy and Brian (or was it Basil, surely not) talked for a long

time about my ideas, showing no surprise but considerable scholarly interest

in the notion of soldierly people being gay through the ages, and asking,

like Miami, some highly technical and academically quite absorbing questions

about the historical variety of the outlaw tradition and its gender constructions.

The

same sort of intelligent interest came from two sources in continental magazines.

Der Spiegel rang up and conducted a lengthy interview in impeccable English,

then wrote it up in highly quirky German, full of witticism and neologism

- I needed Deutsche friends to read that one. And a cool woman from the French

weekly L'Evenement called; we had a long talk, mostly in my fairly limited

French, but it's easier than you might think because almost all of the critical

theory speak we practise at Cardiff is straight from French. The ideological

recuperation situates itself at the site of dialectical interpellation, I

would say and she would hum `D'accord.' As a Brit, I am ashamed to say these

two were the only serious magazine essays on the topic. Apparently no British

magazine or paper does what Der Spiegel or L'Événement and no

doubt other journals around the world, do, break down a new issue for the

intelligent general reader.

But

if that was all varying degrees of positive engagement with the issue, what

of the opposition ? I think you'd put in that category the schlock newspapers

like the London Sun, that source of all things dark; these mostly reran a

condensed version of the Sunday Times story with a joke or two. (`John's not

that little.') That kind of treatment went round the world because Reuter's

Internet service had a boil-down of the Times story out within a few hours:

hence the South China News and other exotic locations - the Darwin Star may

be the most recondite. The Nottingham papers were pretty shirty, of course,

and through the next ten days carried both stir-them-up pieces, one on page

one and a series of outraged letters from members of the Sherwood Forest public.I

got a few of these myself, mostly on small cheap ill-addressed envelopes but

a few from tooled-up members of the nutter community who tracked my email

through the university publicity that had started the whole deal in the first

place.

The

opposition fell into two camps (if I may use that term). One was standard

anti-academic: `What do we pay these people for ? Why doesn't he get on

with finding a cure for cancer ?' I should get such a salary. But most, and

most interesting, were those which revealed by projection the anxieties of

the authors. Most of them referred to children - this really deserves researching,

but I think it's Neurosis Studies, not Robin Hood Research. They accused me

of spoiling the Robin Hood story for children - who presumably were in their

own special and warm care. Or heated care. One guy from Nottingham said that

after calling Robin Hood gay, what's next, calling Father Christmas a paedophile

? A view that bears some thinking about. The projection of anxiety about

sexuality seemed the dominant cause of outrage, not any explicit form of

gay-bashing. The idea of a sexualised Robin Hood itself seemed a perversion.

Those who fostered their anxieties on children - or perhaps on themselves

as still pre-Oedipal - were the most explicit. Most of the correspondents

to the Nottingham Post or to myself were just angry, discommoded, unbalanced,

by this gendering of someone who should simply be gender-free, or at most

male in an unsexualised way. Robin Hood, the stories tell us, never had a

child, never had sexual intercourse with a woman, at most kissed once an impassive

actress at the very end of the film - and then scampered off like a boy.

Was

it, in fact, not the homosexual gendering of Robin Hood that was the problem

for these people, but simply the gendering of Robin Hood. Has he not, like

Peter Pan, Adam and Eve before the fall, ghosts, George Bush, Queen Victoria,

been someone who you could identify with without having to involve yourself

in the bogs and fens of Sexuality ?

Yet

at the same time he is beset - or empowered - by symbols. Deep forest, dark

caverns, towers to be climbed, tunnels to be penetrated; and all that done

with bows, arrows, swords, spears and quarter-staffs, and in tight green tights

at that. The tradition is seething with a strongly coded sexuality, that

is curiously uncoupled from conventional morality because of its coding and

so is in the contemporary American critical language `queer', resistant

to authority like any outlaw - and so if described as `gay' presumably all

the more shocking.

That's

my conclusion at present; and it's one that feeds back into those very same

dull, old, badly printed nineteenth century novels that so much interest

me, and where this started. By making Marian into Mrs Robin Hood, they have

unlocked the Pandora's Box of sexuality. And the only way of closing it,

or at least not opening wide its most volatile apertures, is to constrain

Robin within the decency of man-to-man affect, as in a good public school,

as when Tennyson went on holiday with his chums, and as when Robin and John

clapped each other around the shoulders in a manly, but also womanly, embrace.

In

the last few weeks the remarkable international response (almost a nervous

knee-jerk, or perhaps higher up than that) to the idea that Robin was gay

has been in my view only the pain of recognition of a deep-seated element

in the myth that has always been there, but has only worked through its

subconscious force. Like a dream. Robin has been represented in film as a

conspicuously handsome man, Fairbanks, Flynn, Praed to name the obvious cases

- and in each case also a distinctly androgynous beauty. I suspect the reason

many people find Kevin Costner uninteresting in Robin Hood : Prince of Thieves

is because he has neither the trickster spirit nor the double-gendered beauty

of those other heroes. Though we do see him naked from behind: the camera's

gaze can act on our behalf.

And

one of the amusing things about the Robin Hood myth is that the covert nature

of its sexuality was a major reason for its enormous growth in popularity

in the early twentieth century. As the education system expanded, seeking

texts that could imbue Englishness, decency, masculine values, but were

not like the Arthur legend stained with adultery, many school curriculum

authorities settled on retellings of the Robin Hood story in plain prose

or, equally popular, in simple three act drama - and remarkably this was

as popular in America as in Britain, where Howard Pyle was the lightning

conductor. So the kiddies play-acted in this hygienised environment the man

who fought with arrow and sword and quarter staff, and inter-phallicised

endlessly with his masculine coevals, while Maid Marian drooped about waiting

for the token final kiss, or perhaps just hand-holding. The combination of

powerfully coded sexuality, and overtly asexual text seems central to the

dynamic of the Robin Hood story - all happening in the natural depths of

the richly green productive forest - and it may be that to suggest that sexuality

is in there, and may anyway be of any kind, is to break the taboo on which

the coded dynamics of the heroic saga have depended. I've spoiled it for

adults, not children.

When

Fairbanks, the great star of the hugely profitable 1922 picture, says to

King Richard as he points him towards the maidens, `Exempt me sire, I am

afeard of women', that is the mark of his heroism, the sign of absent sexuality

that, it seems, my semi-innocent thoughts of this summer have through various

multiple mediations brought into both disturbing and intriguing sight.

For

Robin Hood scholars, there are a few fine points to note. The most simplistic

of the media stories have simply replicated the old `quest for the real

Robin Hood' historicism, that totem of humanist individualism that we are

just beginning to escape, at least in the academy; for some journalists I

had suggested that not only was there a real Robin Hood but that he was running

around Sherwood Forest in real pink tights.

And

another nice point for scholars was to note what I scrupulously concealed

from my interrogators, though one of them, in Le Monde, picked some of it

up for himself. It is curious,and I think entirely coincidental, that this

possibly gay Robin has been involved to a considerable degree with the only

two kings in English history thought with some confidence to be homosexual.

One is Richard I, with whom the gentrifying writers of the sixteenth century

firmly link the hero, in order to make his resistance to authority benign,

as he resists bad Prince John in the name of his absent monarch and true lordship.

The Le Monde guy picked up this element on his own and wished it on me, having

me say that Richard had given land to Robin because of their gay connection.

Not so mon brave. Nor did I ever reveal, nor anyone ever have the scholarship

to find out (like by reading my book), that the nineteenth century archivist

Joseph Hunter discovered archives indicating clearly that a man called Robyn

Hood was in fact valet de chambre to king Edward II, certainly a homosexual,

some of the time at least, and Hunter thought that this Edward is the `comely

king' of the Gest of Robin Hood, the major text of the medieval realisation

of the outlaw. I think to speculate about those connections would be an entirely

illegitimate way to read Robin Hood as a gay figure; but I still think that

his story is available as a way of realising the values of the male gay world,

its focus on the dangers, comradeship, festivals and feelings to be found

in an exclusively male world. I believe that is one of the possible, indeed

rather forceful, readings of the outlaw myth, and one that in the nineteenth

and twentieth centuries has had some significance as one of the reasons for

the continuing popularity of the elusive hero, always disappearing into the

forest and always eluding the constraining simplicities of authority, identity,

sexuality.

Texts

can be constructed by their audience; and you can find things out through

motion. The responses to my partly playful but increasingly serious comments

on the gay Robin Hood have led me to think there is much more in this issue

than I originally knew - consciously knew, that is. The book of research

essays on Robin Hood I am now preparing will conclude with one entitled `Gendering

Robin Hood'.

(C) Stephen Knight,

1999

Photo (C) Copyright -- Allen W. Wright, 2003

This photo of Stephen Knight comes from a production of the Ben Jonson play

The Sad Shepherd staged at the 2003 Robin Hood academic conference. Stephen

played the evil witch Maudlin magically impersonating Marian. As Maudlin,

he had a big nose and as Marian, he had the blonde wig scene here. He was

utterly delightful in this part, and it's nice to see professors with a sense

of fun.

Contact Us