The Forest and Forest Laws

After William, duke of Normandy, conquered England in 1066 and became its king, the concept of the royal forest was established. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle had this to say of William I:

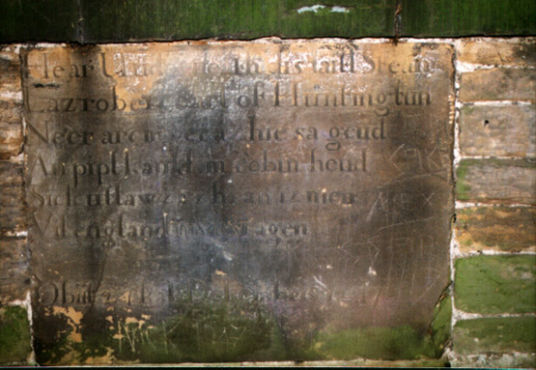

He made great protection for the game

And imposed laws for the same,

That who so slew hart or hind

Should he be made blind.

He preserved the harts and boars

And loved the stags as much

As if he were their father.

Morever, for the hares did he decree that they should go free.

Powerful men complained of it and poor men lamented it,

But so fierce was he that he cared not for the rancour of them all,

But they had to follow out the king's will entirely

If they wished to live or hold their land,

Property or estate, or his favour great.

Quoted in The Royal Forests of Medieval England by Charles R. Young, pp. 2-3.

Actually, Sherwood Forest itself is not mentioned in the 11th century survey, the Domesday Book. But certainly by the middle of the 12th century, all of Nottinghamshire north of the river Trent was under forest law, as was much of the neighbouring county of Derbyshire.

Forest law was a separate set of laws imposed on the Royal Forests -- nominally to preserve the important game animals and their habitats. There were restrictions on taking wood, building, what animals you could keep and so on. (Dogs, when not outright forbidden, had to be "lawed", with some toes trimmed so they would not chase after the deer.) It was also illegal to carry a bow in the forest.

The most notable provision was that against killing the king's deer. Late in Henry II's reign, his laws implied you would be killed on the third offence. By the time of King Richard the Lionheart (specifically 1198 AD), the penalty for killing a deer was mutilation -- where the law would remove your eyes and certain other delicate parts.

These days Robin Hood stories often feature the hero rescuing a starving peasant who killed a deer from the foresters who patrolled the forests enforcing the laws. There are reports of corruption among the foresters, although I've heard talk that some would help villagers where they could. Click here to see a picture of Blacke

Dickon, a medieval forester in Sherwood. In the Robin Hood stories, the foresters might threaten to kill the poacher or chop off his hands or fingers. One story says Robin was outlawed for killing a group of foresters. Robin is often seen to feast on the king's deer (or venison as deer meat, or originally the meat of any hunted animal, is called) - laws don't matter much to an outlaw. But other tales suggest that Robin's father, or perhaps Robin Hood himself, was once a forester.

Historically, death or mutilation was the maximum punishment -- often times, offenders were imprisoned and fined. The fines and fees were a great money maker for the crown and forest officials. And the wealthy and powerful often wanted to curb the forest laws as much as the poor did. One 12th century writer wrote "The forest has its own laws, based, it is said, not on the Common Law of the realm, but on the arbitrary legislation of the King; so that what is done in accordance with forest law is not called 'just' without qualification, but 'just', according to forest law."(quoted in Young, p. 66) Many of the barons who rebelled against King John were concerned about the forest laws.

In 1217 (the year after King John died while Henry III was still a child), a Charter of the Forest -- the little charter compared the great charter or Magna Carta -- was issued that restricted many abuses. It was reissued in 1225 with some modifications. The tenth provision of the charter was:

No one shall henceforth lose life or limb because of our venison, but if anyone has been arrested and convicted of taking venison he shall be fined heavily if he has the means; and if he has not the means, he shall lie in our prison for a year and a day; and if after a year and a day he can find pledges he may leave prison; but if not, he shall abjure the realm of England."

Also by the 1220s, the boundaries of Sherwood Forest were greatly restricted with the river Trent as the southern boundary and the river Meden as the northern one. The size of the forest on the east and west was greatly reduced. It stayed at those boundaries for the rest of the Middle Ages, but "Sherwood Forest" today is far, far smaller.

The

defining characteristic of a forest is that it was governed by forest laws.

Not all of Sherwood was not a heavily wooded area. There were large fields,

meadows and even towns inside of Sherwood.

Contact Us