And where would Robin Hood be without his faithful band of outlaws? Historians who go looking for a real Robin Hood have also looked for historical Little Johns, Friar Tucks and others.

Little John is nearly as important as Robin Hood in the early tales. There are several historical candidates for Robin's chief lieutenant.

The best known comes from Hathersage in Derbyshire. Little John's supposed longbow was once on display there, and the outlaw has a grave in a Hathersage churchyard . In the grave was a bone which would belong to a very tall man. On the longbow is the name "Naylor", said to be Little John's last name, Holt thinks it may have been put there by Colonel Naylor in 1715. The association with Hathersage goes back to the 1600s. While certainly good for the tourist trade, there is no definite proof that the bow or grave belonged to a historical Little John.

The ballad "Robin Hood and Little John" says that the outlaw's true name is John Little. And John Bellamy in Robin Hood: A Historical Inquiry has found many candidates with this name.

They include John Litel, sheriff of London on and off between 1354-1367. Others were less law abiding. A criminal John le Litel was part of band of raiders who made off with 138 pounds in 1318. In June 1323, a Littel John was part of a group who made off with deer in Yorkshire.

Bellamy's prime candidate is actually named Little John, a sailor in command of a royal ship in the 1320's. This one lived at the same time as his main Robin Hood candidate, but there's no evidence that they knew each other or that this John was an outlaw.

John Matthews, on the other hand, seeks a mythological origin for Little John and the other Merry Men. He suggests that Little John may have been a forest spirit.

Most Robin Hood stories these days are set in the era of Richard I. There were no friars in England back then. It doesn't help that the early ballads are set in later times, because Tuck's not in them either. But he does pop up as Frere Tuk in a relatively early fragment of Robin Hood drama, circa 1475, but he was not the fat, jolly friar we know today. Perhaps that's because this Tuck might have been inspired by a real person.

Twice in 1417, royal writs demand the arrest of an outlaw who led a band which robbed, murdered and committed other acts of general mayhem. One report says he "assumed the name of Frere Tuk newly so called in the common parlance." As Holt explains "the men who drafted the writs of 1417 had apparently never heard the name Friar Tuck before." A letter in 1429 says Tuck is still at large, and mentions his real identity -- Robert Stafford, chaplain of Lindfield, Sussex.

This chaplain may have employed an alias from a pre-existing legend, but it's quite possible that he was the first to use the name of Tuck.

And what of the jolly friar of legend? It was a stock character in the May Games and morris dances, a sometimes partner of Maid Marian. As Dobson and Taylor put it, an "altogether more jovial and buffoon-like character." They suggest that perhaps the stories of a real outlaw were combined with the friar of the May Games to make the outlaw we know and love.

The outlaw currently known as Will Scarlet was known by a lot of names in the early stories -- Scatheloke, Scarlock, Scadlock, and Scarlett. John Bellamy has found a few real ones.

A William Scarlet was one of many who received a pardon in 1318. And two years earlier, there's a record of a William Schakelock, soldier in the Berwick town garrison in 1316. Both these, and they may be the same person, Scarlets fit nicely with the time period of the 1320's Robin Hood, Bellamy's choice for the outlaw leader.

He dismisses the most interesting Will Scarlet as being too early for his favourite Robin Hood. In 1286-7, William Schirelock (or Shyreloke) was a "novice of St. Mary's Abbey, York, who was allowed to depart because of a crime imputed to him." This Scarlet was at the same Abbey which played a major role in the early tale known as the Gest.

Interesting, but like most "real" candidates for Robin and his band, there aren't enough details to conclude these men were definitely inspirations for the legendary character.

Just as Robin Hood borrowed elements from other outlaw legends, Will Scarlet's 17th century "origin" tale (composed long after Scarlet's first appearance in the Robin Hood legend) winks at other legends too. In the ballad Robin Hood Newly Revived, also known by the more descriptive title, Robin Hood and WIll Scarlet, Will says that his name is "Young Gamwell". Gamwell, to be named Scarlet at the ballad's end, says that he was outlawed for killing his father's steward. Will is a nephew, or cousin, of Robin Hood. And the hero of different outlaw romance, Gamelyn, could be considered a relative of the Robin Hood legend. Gamelyn was disinherited and outlawed for, among other things, killing his father and brother's porter. Will Scarlet has borrowed from the Gamelyn story, and perhaps another outlaw tale called Robin and Gandelyn.

Like Tuck, Marian isn't in the early ballads and probably joined as a character in the May Games. In those traditional celebrations, she was sometimes portrayed a very "free" woman, often played by a man in drag. She probably comes from the medieval French pastoral romance of the shepherd and shepherdess Robin and Marion. When Robin Hood plays started being performed at the celebrations she was a part of, it was only natural for her to join Robin Hood's legend as his true love. I don't know if there's any truth behind the early French stories of a Marion.

But in his Elizabethan "Huntingdon" plays, Anthony Munday makes Marian an alias employed by Matilda Fitzwalter (or Fitzwater). A popular romance at the time was the legend of King John pursuing Matilda (or Maud), daughter of Robert FitzWalter. FitzWalter was accused of plotting to assassinate King John and was outlawed in 1212. When he fled to France, it seems that FitzWalter justified his actions by saying the king was after his daughter and plotted to kill his son-in-law. King John was lecherous, but some historians don't believe Fitzwalter's version of events. FitzWalter led the Baronial rebellion against John in 1215.

Munday also wrote a 1615 pageant for the Lord Mayor's Day in London. Here, Fitzwater became Fitz-Ailwin and made Marian the daughter of London's first Lord Mayor (who lived in Richard I's day).

The name Matilda is interesting. That's the name of the wife of Robert Hood who lived in Wakefield in the 1310's (possibly the same man as the Robyn Hood of the next decade). Also, the name of the real Earl David of Huntingdon's wife was Maud or Matilda.

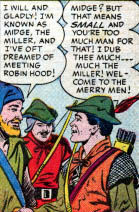

Much appeared in many of the early ballads. It sounds like an alias at best. I don't know of any historical Muchs. Then again, Little John, Will Scarlet, Robin Hood? They all sound like aliases or made-up names. And that's a good reason to take all this "real Merry Men" stuff with a grain of salt.

You might want to take another grain of salt when digesting the mythological approach. Even though in modern versions Much is small, John Matthews posulates he might have been originally been "a primeval giant, or a demi-god turning the mill-wheels of the gods." Much was strong enough to lift Little John in an early ballad, but I see little evidence to suggest such supernatural origins.

Sir Richard isn't really a Merry Man. He's a knight from an early ballad. In A Gest of Robyn Hode, Robin loans money to help a poor knight pay his debt to the abbot of St. Mary's in York. Robin recovers his losses by robbing monks from the abbey. In another story in the Gest, Robin and his men hide in the castle of Sir Rychard at the Lee who is said to be the knight they had helped.

Holt says the story of the knight and abbot is the most original element in the early Robin Hood legends. Bellamy uses the Gest as his gospel in hunting out real Robin Hoods. So, of course, he finds a few real Richard at the Lees.

His main candidate is Richard de la Lee, a parson near Doncaster (and Barnsdale) who was constantly in debt. This Richard is mentioned in 1319-21, at the same time as Bellamy's other candidates for historical characters behind the legend. But unlike his legendary counterpart, he was not a knight.

Bellamy goes onto suggest that the Gest may have been "family propaganda" for a Sir John atte Lee, who was in political hot water in 1368. The theory goes that somehow his reputation would be enhanced by tying a relative in with legendary outlaws and cut-throats. Dobson and Taylor point out the flaws in Bellamy's argument.

However, if the Gest of Robyn Hode is "political propaganda", it seems to have been propaganda of a kind so esoteric that it has successfully defied detection through the centuries, until Professor Bellamy himself has brought it to light.

(Dobson and Taylor, p.ix-xx)

As with Robin Hood, most of our searches for the heroes behind the legend is mere guesswork.

Perhaps we'll have more luck as we search the historical records for Robin Hood's foes.

Contact Us