The Sheriff of Nottingham

When it comes to the villains of Robin Hood, one title is at the top of the list, the Sheriff of Nottingham. But in the time of Robin Hood, the town of Nottingham did not have a sheriff. The first sheriff of Nottingham was created in 1449, about 70 years after the first literary reference to Robin Hood. So, were there no historical sheriffs for a historical Robin Hood to fight? Not exactly.

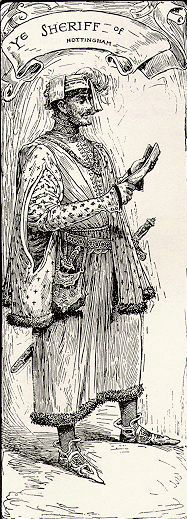

Louis Rhead's classic illustration of the sheriff. Even though the town itself did not have a sheriff until the mid-15th century, the shire of Nottinghamshire had one for centuries before that. And the sheriff of the county would have been called the sheriff of Nottingham by some. During the period of Robin Hood, the sheriff would have been in charge of both Nottinghamshire and neighbouring Derbyshire. (Also, in 1189, Prince John granted that Nottingham - the town - would have a town "reeve" that would hold many sheriff-like responsiblities for the town itself. In 1449, and for centuries afterwards, the town was essentially considered a county in its own right, and the term "sheriff" was then officially applied to both the Nottingham town and Nottinghamshire officials.)

The sheriff was, for the period most commonly depicted in films and children's novels, an unpaid position. In fact, the sheriffs had to pay the king a yearly sum to keep their offices. This sum was called the "farm" of the county. The sheriffs usually made far more from their various duties administering the shires (like collecting taxes) than the crown asked for. In 1204, King John said the sheriffs weren't expected to keep any of the county's revenue. That didn't matter because the sheriffs didn't report all of their income, especially from such sources as being bribed to look the other way, arranging false arrests and so on.

In 1170, Henry II led an inquest to make the sheriffs a group of professional administrators. King John held an inquiry in 1213. But there are tales of corrupt sheriffs for centuries to come. Dobson and Taylor among other Robin Hood historians say that perhaps tales of many corrupt sheriffs combined to make the nameless adversary of Robin Hood.

Contact Us