Green Arrow's Dividing Line

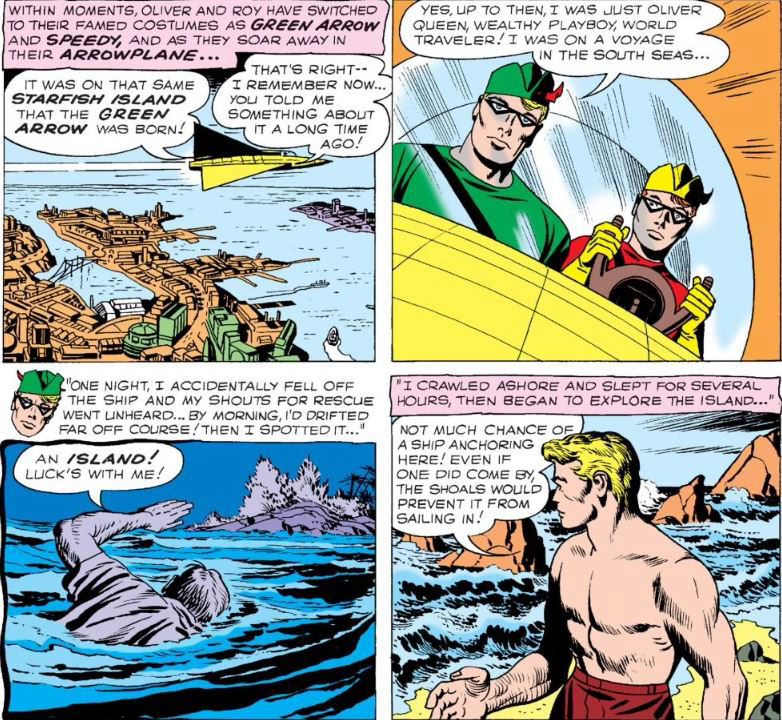

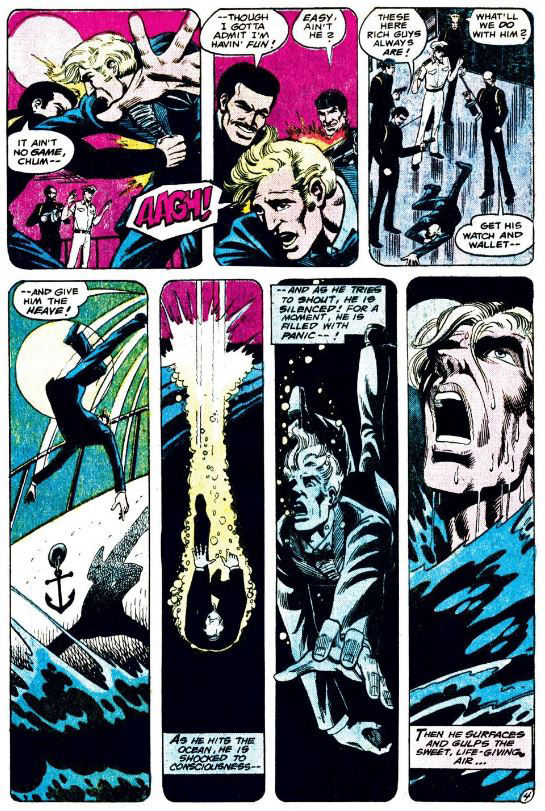

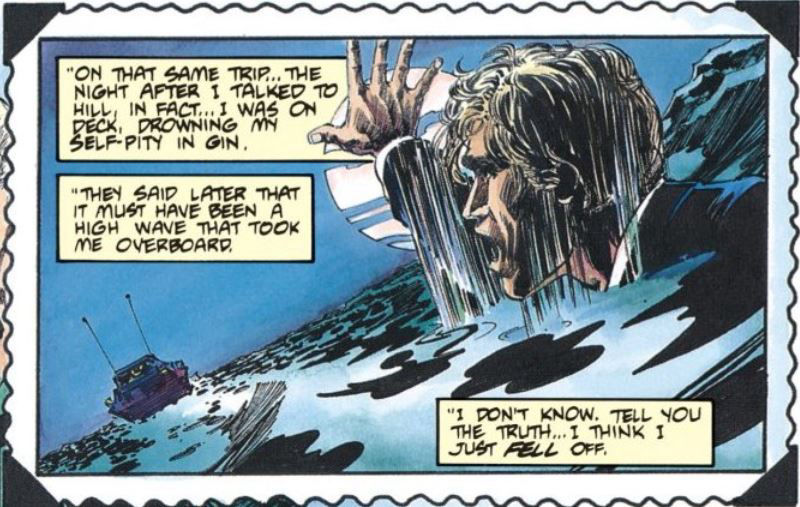

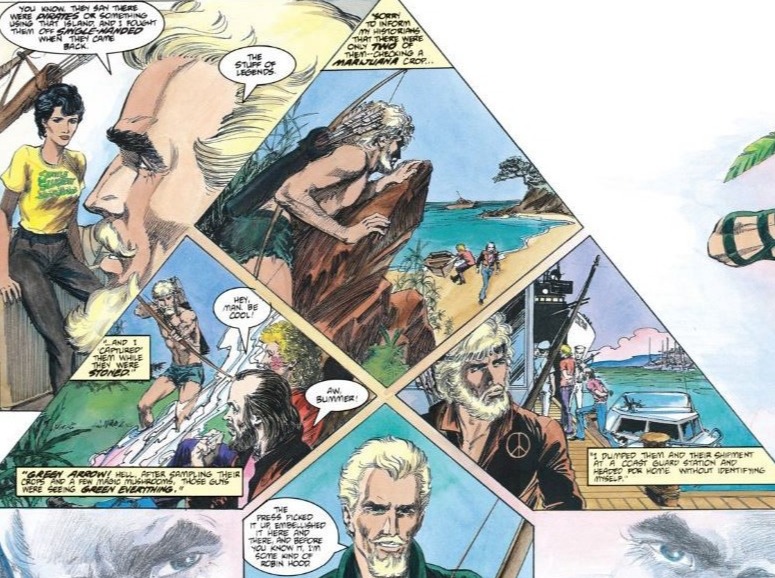

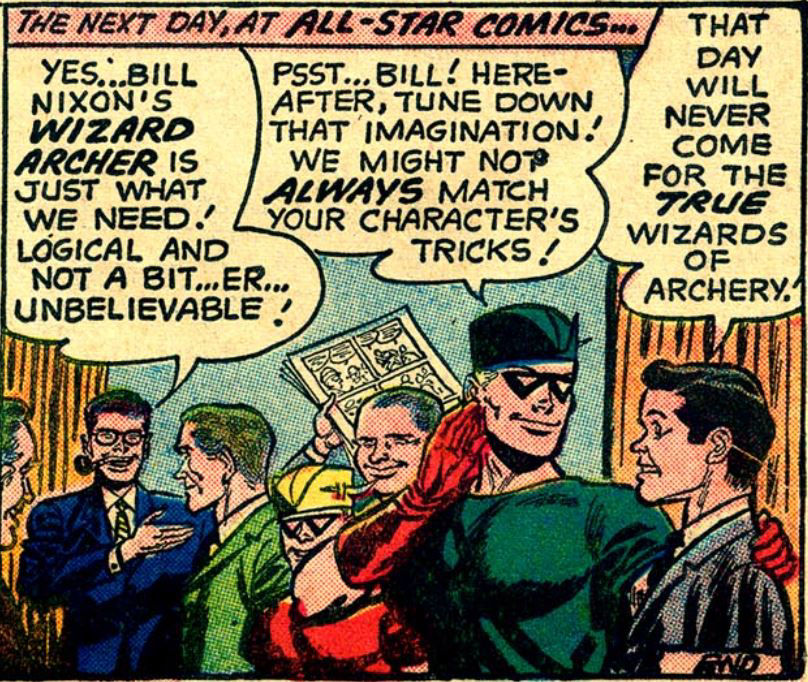

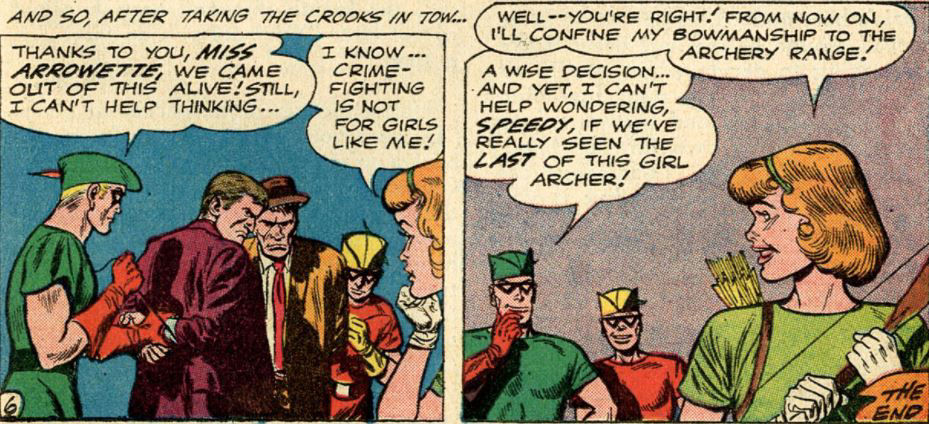

There isn’t a lot to separate the early Silver Age Green Arrow from his late Golden Age counterpart. The stories were a bit slicker and more polished than his earliest appearances. They were a bit simpler too.

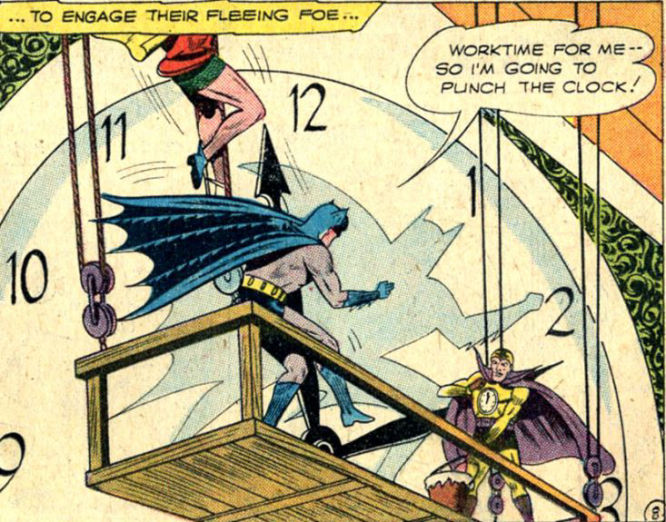

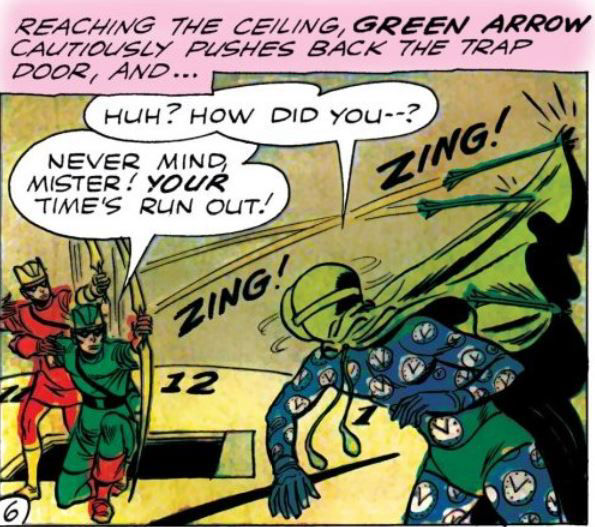

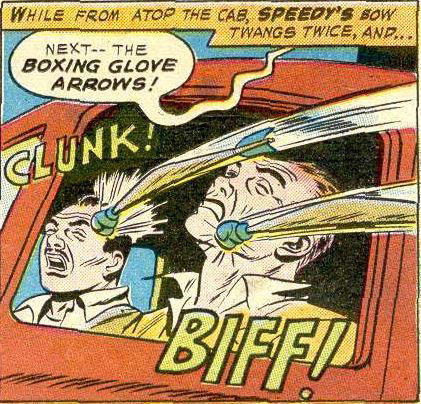

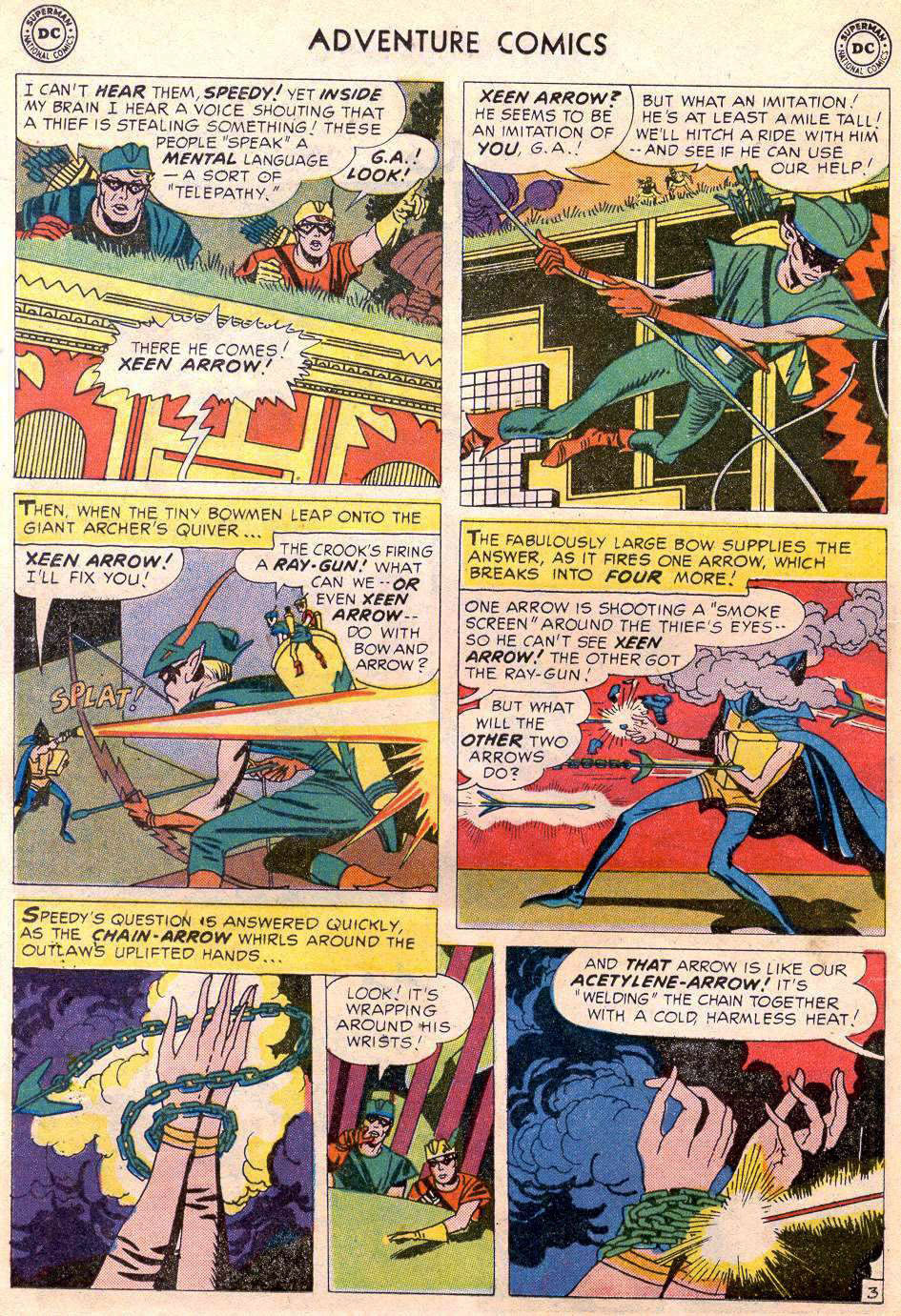

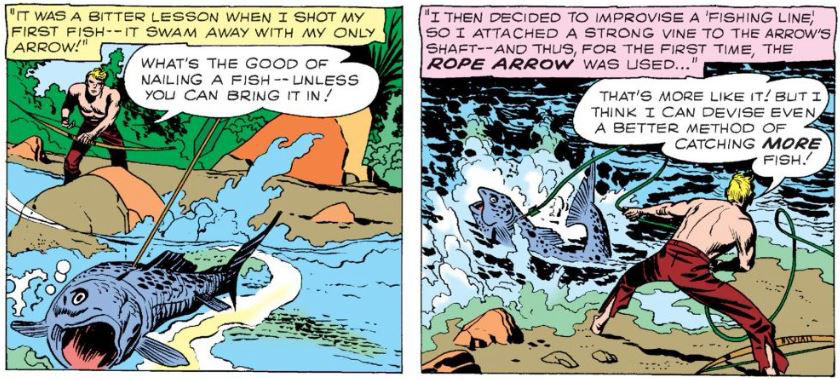

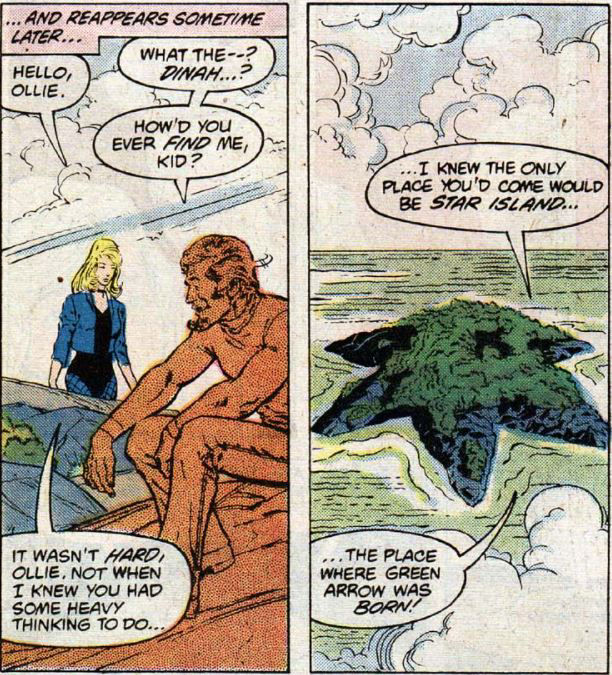

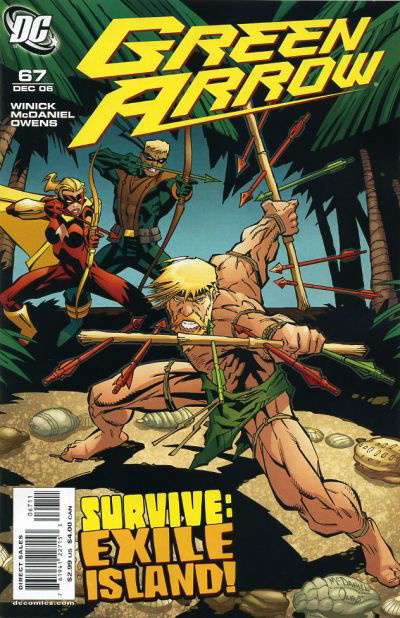

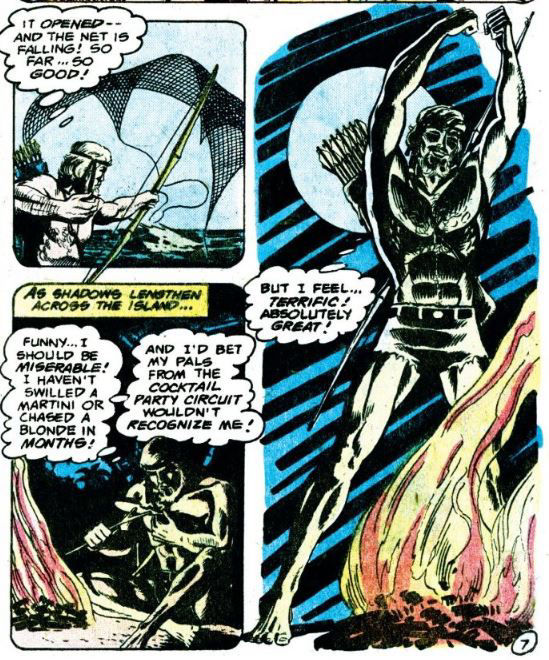

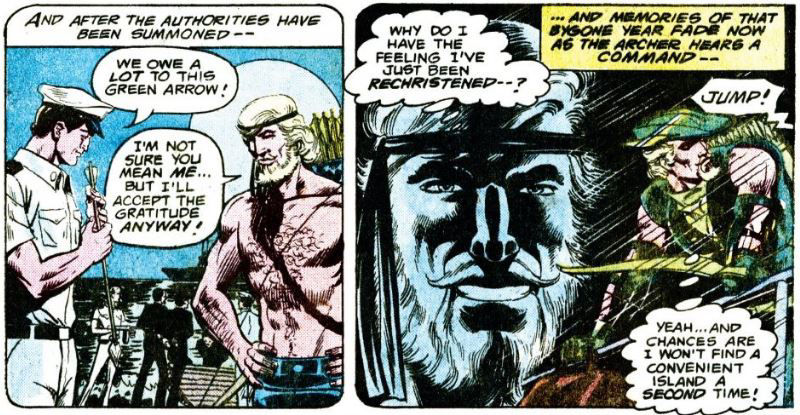

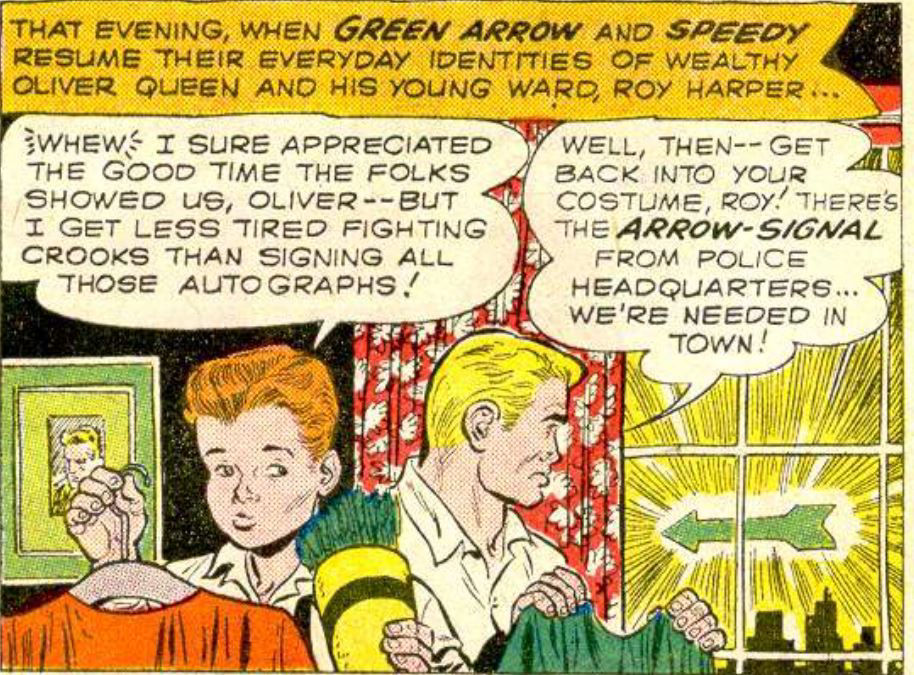

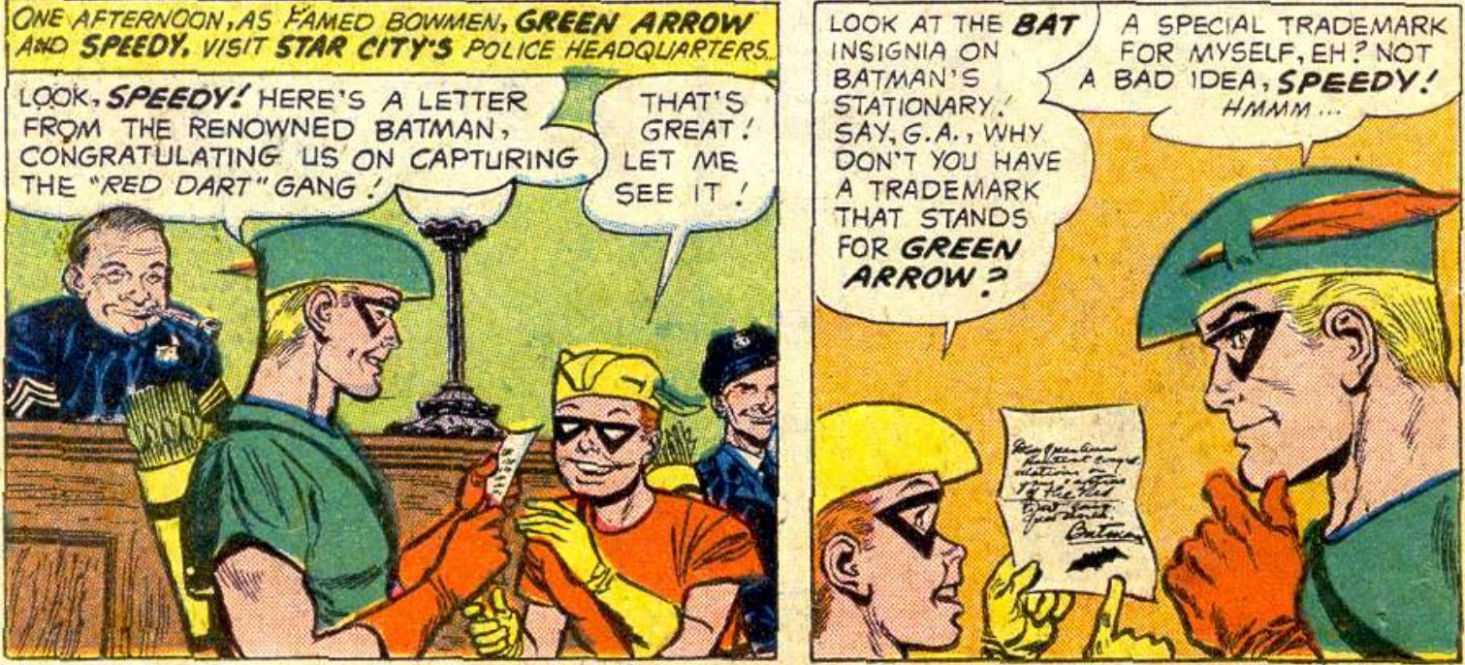

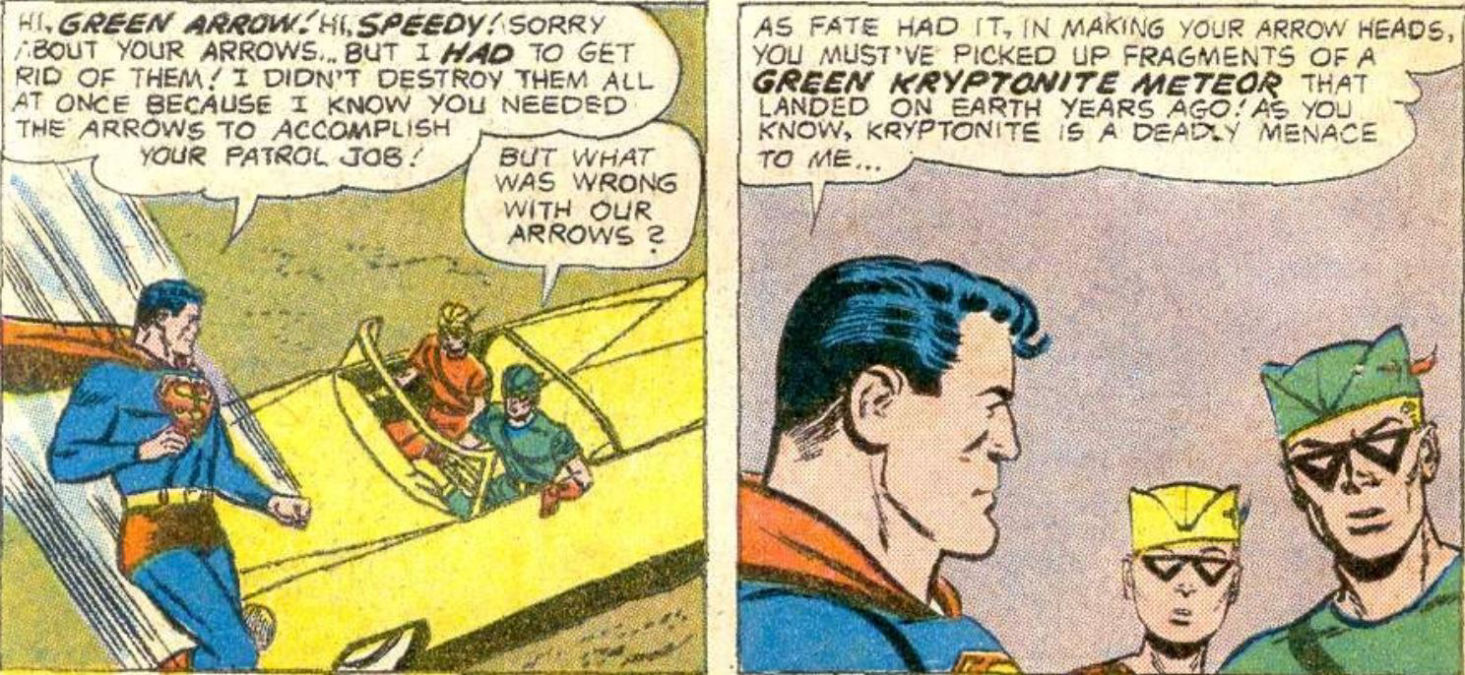

By 1947, Green Arrow had already expanded his arsenal to include the infamous Boxing Glove arrow. The trend continued into the 1950s. Often it feels like the whole point of the story is to introduce as many trick arrows as possible. In “Green Arrow’s Last Stand” from Adventure Comics #254, we are treated to the two-radio arrow, the fountain-pen arrow, the dry-ice arrow, the flare-arrow, the balloon arrow, the boomerang arrow, the two-stage rocket arrow, the net-arrow, and the siren-arrow – all in just six pages. You almost wonder if the 1960s Batman TV series with its deliberately campy references to absurd devices like “Bat Shark Repellent” was thinking as much of Green Arrow as Batman.

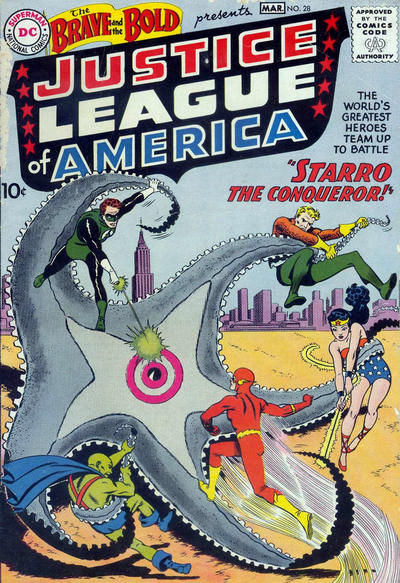

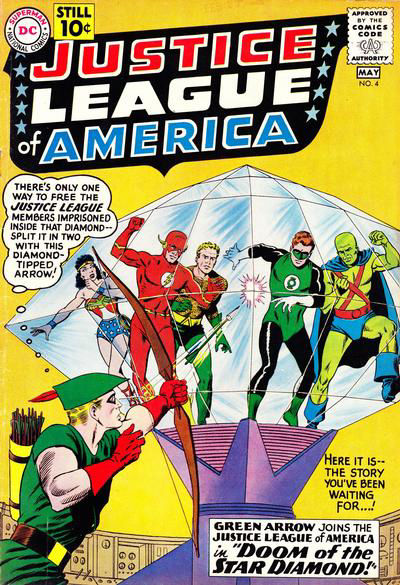

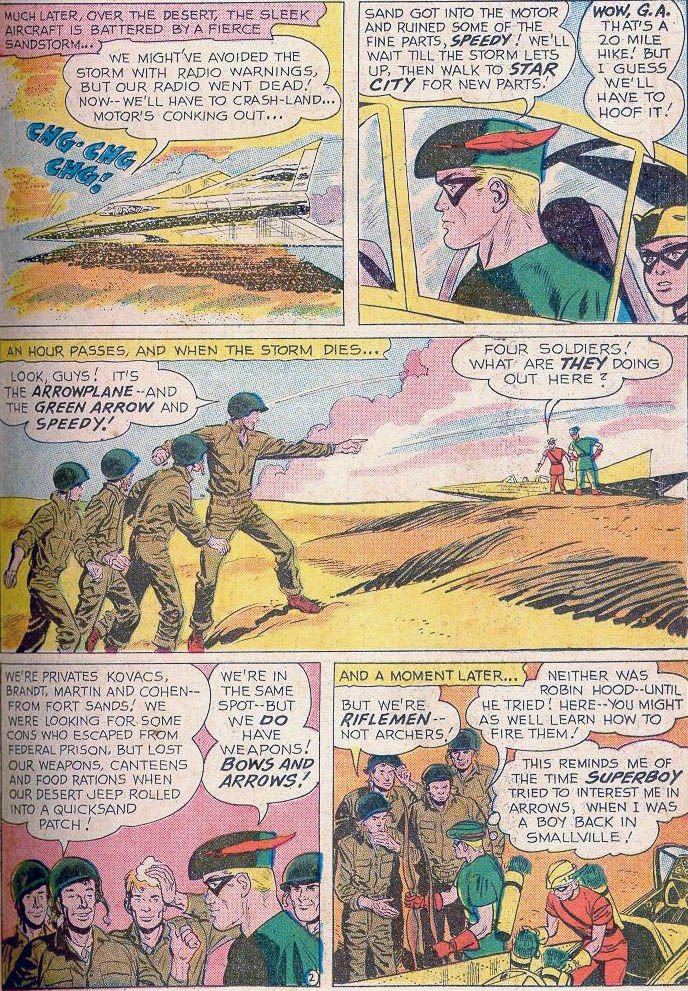

One influence on the stories was a matter of space. Regular sized comics cost 10 cents in 1941 – and they still cost 10 cents in 1961. But you got a lot less for your dime. 1941’s More Fun Comics #73 had a 12-page Doctor Fate story, an eight-page Green Arrow story (his first), a six-page Radio Squad story, an eight-page Johnny Quick story, a two-page text mystery story, a six-page Clip Carson story, a 10-page Spectre story and an eight-page Aquaman story (also his first). That’s 52 comics pages and two text pages. By Adventure Comics #250, 10 cents would buy you a 12-page Superboy story, a six page Green Arrow story, a six page Aquaman story, two educational comic pages, one-and-a-half humour comic pages and one text page of jokes, That’s 27 comics pages and one text page. In his 1940s hey-day when Green Arrow had the cover feature of More Fun Comics, his stories could run 13 pages. Even as a backup feature, his stories would be eight to ten pages.

Beginning with the mid-1950s, his stories would only be between six-and-three-quarter pages and five-and-three-quarter pages. Six pages is not a lot of space for a full and complete story. It was, however, enough space to showcase some of his increasingly bizarre trick arrows.

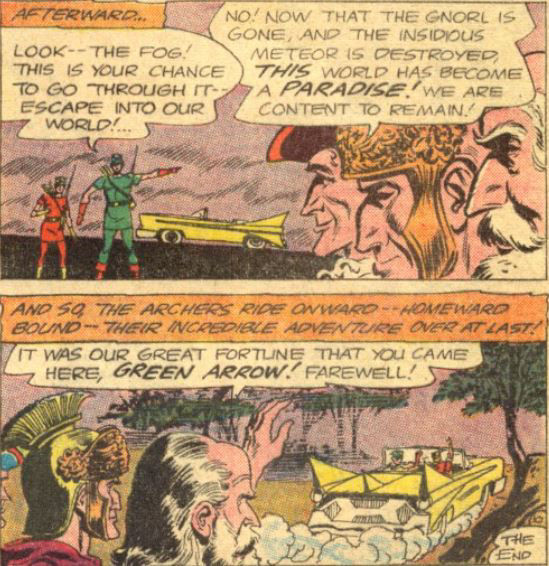

Green Arrow’s stories do increase back to nine-and-three-quarter pages beginning with World’s Finest Comics #134 (June 1963), but that’s because now the comic only had two superhero features instead of three. Green Arrow and Aquaman supporting stories would appear in every alternate issue. But this size increase lasts less than a year, the last original solo Green Arrow story for several years would appear in World Finest Comics #140 – appropriately titled “The Land of No Return”. The following issues would have reprinted stories as the supporting features.

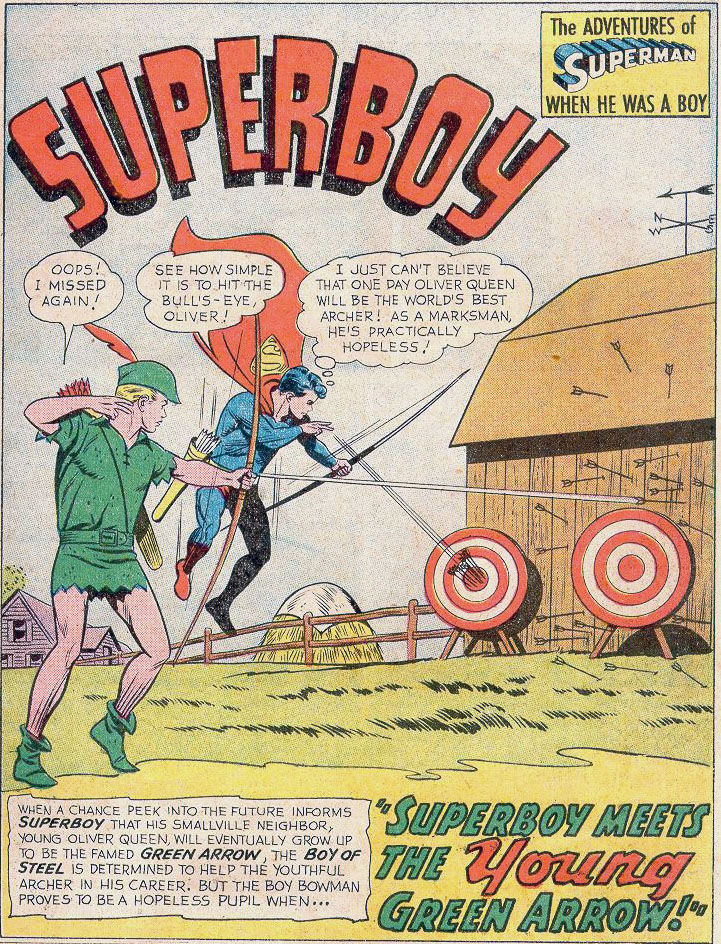

The most commonly referenced dividing line between the Golden Age and Silver Age Green Arrow is an artistic one. Green Arrow’s co-creator George Papp had been in the army during World War II, but once he returned in 1946 he resumed drawing Green Arrow until 1958. In addition to drawing the Green Arrow feature, Papp was drawing Superboy stories in Boy of Steel’s self-titled comic. Papp was becoming THE Superboy artist. So, in 1958 he took over drawing the lead Superboy feature in Adventure Comics. Someone else would have to draw the Green Arrow stories in Adventure Comics and World’s Finest. And what a someone it was -- Jack Kirby.

Contact Us