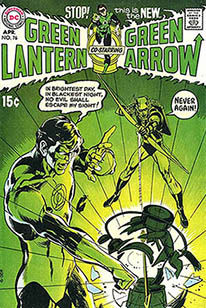

So one day when I realized that Denny O'Neil and I were probably coming to the end of the line with the Green Lantern / Green Arrow books, because one they weren't selling well. Or else the perception was that they weren't selling well, but in fact what was happening was there were teenagers all over America that were buying comic books out of the back of the wholesalers, and those books were being called destroyed, because the industry had gotten into doing this 'affidavit return' policy. So that they didn't have to return the [unsold] books or even slice off the titles. They would just depend on the local distributor to say they had destroyed the comic book. Well, local distributors were not destroying the comic books, they were selling them to teenagers out of the back of the distributor's shop for seven cents [cover price was 15 cents]. And these kids would then take those comic books by their favourite artist -- or the artist that would sell like Berni Wrightson and myself and Barry Smith and all those folks and they would sell them to their friends at motels or in their father's garages. Sell them to the neighbourhood kids for two dollars and five dollars according to what the quality was, because those kids could not find those comic books in their neighbourhood, because these kids were buying up them up out of the back of the wholesaler. And those kids who did that became the first tier of direct sales market comic book stores.

AWW: Which is what industry is today.

NA: That's right. Those guys are still around. Not all of them, many of them died. You just have to look at the guys wearing the jeans jackets and silver hair with pony tails and leathery skin and those are the guys that began the direct sales market by buying comic books out of the back of the wholesalers and the wholesale reporting them as being destroyed. So when DC Comics said "Gee, I don't understand, Neal. Everybody's writing letters about Green Lantern/Green Arrow, everybody loves it, college students are writing letters, high school students are writing letters, but it's not selling that well. I don't understand." Well, it was selling like hotcakes -- like hotcakes. I sign, when I go to conventions, mint condition copies of those books. Because people put them in boxes and store them away and sell them. You can buy those books for as much as $400 a copy now. You've got very smart people who are storing that away or selling them for $2 or $5 in those days. It was a very corrupt and very strange business, and the direct sales market -- the no-return market -- saved it, but they saved it because they had corrupted it.

AWW: That's funny that the corrupting influence becomes the official saviour.

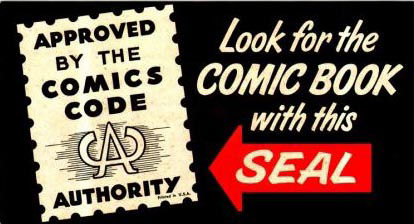

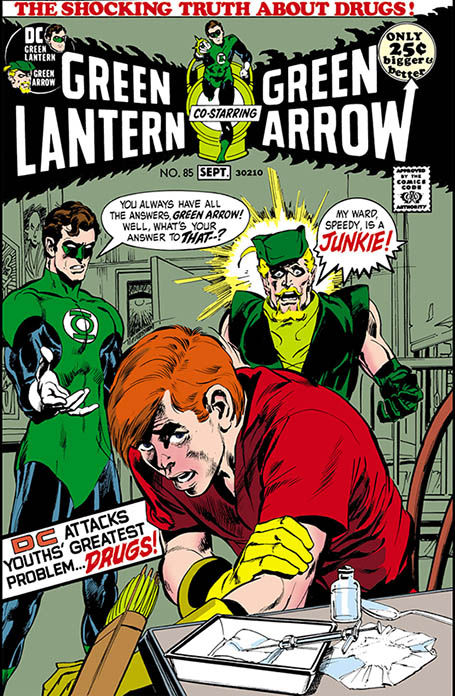

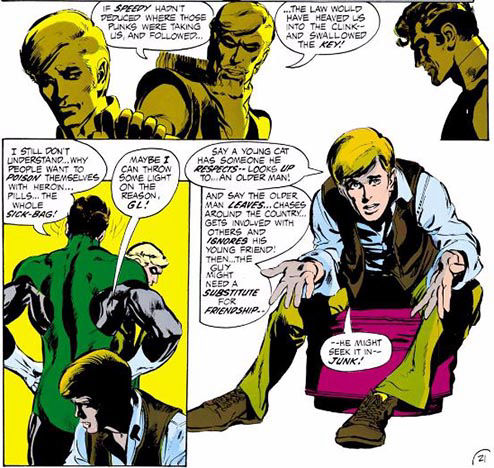

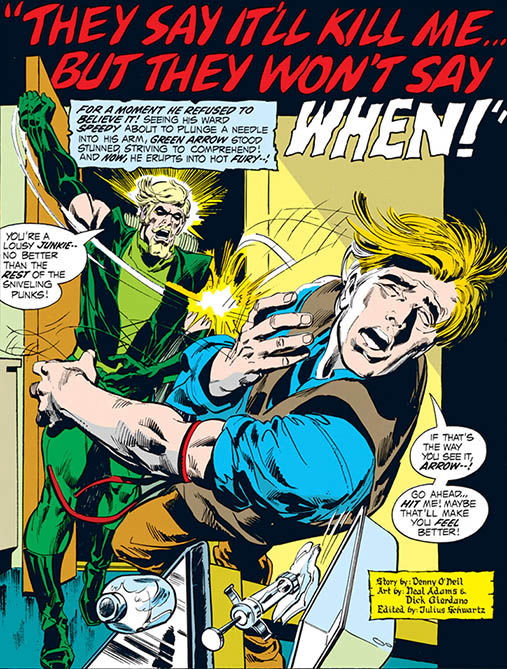

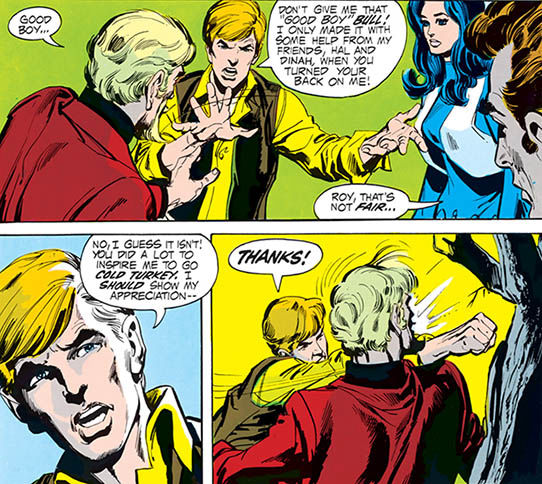

NA: That's right. Anyway, it was very clear we were coming to the end of our run. Denny wrote a story on overpopulation. And I thought "Unh-unh, this is the end. This is not a good story. We don't want to do this." You could fit the population of the Earth into the state of Texas and have room for everybody. It just was a bad subject. I remember those days. People were having vasectomies and all kinds of weird s--t was going on. So, I figured I'm watching the end of what we're doing. And I thought there's two things we didn't do, first we didn't get a Black superhero and I was determined to do that. Second, we hadn't handled drugs. And therefore, we had to kill the Comics Code, because that was the only way to do drugs. So I went home and, on my own, pencilled and inked and then lettered that first drug issue [cover] with Speedy [Green Arrow's former sidekick aka Roy Harper] as a junkie. And I handed it into my editor and he dropped it like a hot potato and said "What the hell are you doing, Neal? You're causing trouble again." I said "No, we oughta print this, Julie [editor Julius Schwartz]." He said "We'll never print this, it won't pass the Comics Code." He said, "First of all, Neal, this will never be printed -- never be printed -- and second of all, I will never pay you for it." I said "We'll see."

Contact Us